A masterclass in political failure

Dutton’s Liberal–National Party is out of time, out of touch, out of ideas, and out of momentum. And it’s not a winning formula.

The third week of the federal election campaign has confirmed what many political observers suspected a couple of weeks ago: the Liberal Party’s campaign is not just failing – it’s falling apart. And while the previous week was best described as disastrous, this week has arguably been even worse. Where most governments benefit from incumbency by running disciplined, focused, and generally positive campaigns – touting achievements, pushing hopeful messaging, and strategically avoiding pitfalls – what we’re seeing from Peter Dutton and the Coalition is the opposite: a miserable, mistake-ridden, directionless, and relentlessly negative campaign that appears to lack the energy or coherence required to inspire confidence with the electorate.

It’s not just the gloom-laden dystopian talking points about Australia being on the brink of collapse – it’s the absence of a compelling alternative vision. The Coalition has placed all its eggs in one basket: trying to convince the electorate that everything – absolutely everything – is so bad, and only getting worse, and that the Labor government is to blame for absolutely everything. Nothing is good… it’s all so terrible.

Yet, as comprehensive as this message has been, it’s a message that’s failing to have the impact that was intended. The supposed dystopia Dutton wants Australians to believe in simply doesn’t reflect reality. The sun still rises, people still go about their lives, and while challenges exist – as they always do – Australians don’t appear to be buying into the apocalyptic narrative being peddled by the Coalition, if the current opinion polls are to be believed. It’s a strategy that feels increasingly out of touch with how most voters actually experience the world.

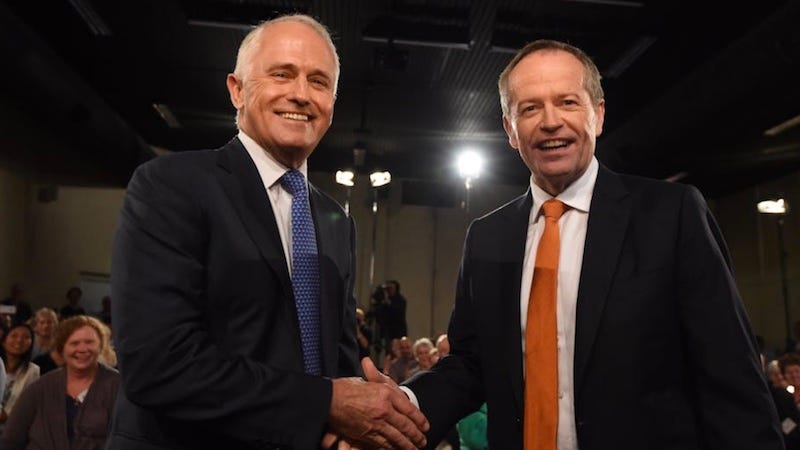

At the centre of this malaise is Dutton himself – a leader whose performance has been characterised by mistakes and a lack of political groundwork, not just during this campaign, but for this entire parliamentary term. For someone who has had three years to prepare for this campaign, Dutton seems astonishingly unready and underprepared. Compared to previous opposition leaders: Bill Shorten used his six years to criss-cross the country, regularly subjecting himself to hostile town halls, testing policy ideas, and building a campaign machine. Anthony Albanese, while less aggressive and productive during his time as leader of the opposition, still made use of every available moment in opposition to refine his messaging and build credibility.

Dutton, on the other hand, has spent the bulk of his time in the right-wing media bubble – appearing regularly on Sky News and 2GB, ignoring critical outlets such as SBS, denouncing the ABC, and speaking only to a narrow audience already predisposed to support him. This isn’t a winning strategy for an opposition leader; it’s a regression and the wiser heads within the Liberal Party – if there are any who still exist – should have worked on broadening the experience of Dutton far earlier.

Leadership demands visibility, flexibility, and effort. But Dutton frequently disappeared from public view when the going got tough. He’s failed to test ideas in the public arena, avoided uncomfortable questions, and relied instead on ideological comfort zones filled with culture war rhetoric and attacks on ‘woke’ media and ‘indoctrinating’ school education across Australia. This hasn’t sharpened his message, it’s done the opposite: it has dulled his appeal. It has left him unchallenged, untested, and unprepared for the rigours of a national election campaign. What’s emerging now is the result of that neglect: a leader lost in the fog of his own negativity, unable to present himself as a credible alternative Prime Minister. Why did nobody within his team prepare Dutton for this election campaign? Why did nobody notice the clearly ringing alarm bells?

And what would a Dutton government even look like? At best, it would be a Morrison government redux – without even the modest veneer of competence, considering the Morrison government left behind a legacy of dysfunction, secrecy, and poor administration. The idea that voters are crying out for a return to that style of governance that they clearly rejected at the 2022 federal election is delusional. For all the Coalition’s attempts to stoke fear and division, the one thing it has failed to provide is a coherent sense of purpose – the raison d’être behind their bid for power. Once any of Dutton’s campaign rhetoric is peeled back, there is no reason in this bid: it appears to be power for the sake of power.

This is what makes this campaign not just ineffective, but potentially one of the worst opposition efforts in recent memory. There’s no grand contest of ideas, no bold vision to debate, no clear sense of what the Liberal Party actually stands for beyond not being Labor, endlessly criticising the government, and wanting to be the government. Even those who might be sympathetic to conservative principles are being left cold by a campaign that seems designed more to inflame than to inspire. And as pre-poll voting opens this week, time is rapidly running out to turn things around.

Australians want a government that functions and works for them – not one that just constantly offers blame. They want leadership – not constant complaints about the media or dog-whistling about woke culture. We’ve been here before – through Scott Morrison – and it seems that the Liberal Party picked up all the wrong lessons from the 2022 federal election result, which they comprehensively lost.

And while the Labor Party is not promising any type of revolutionary reform or providing anything outstanding to the electorate, at least it’s offering a coherent and largely positive agenda. For the Liberals, this campaign has devolved into an excellent case study about what happens when an opposition fails to do the hard work, refuses to grow beyond its ideological comfort zone, and underestimates the intelligence and optimism of the electorate.

The worst opposition campaign in political history?

It’s a question that keeps coming up – among journalists, political analysts, and increasingly from the public itself: is this the worst election campaign run by an opposition in modern Australian political history? As the third week of the 2025 campaign draws to a close, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the Liberal Party’s performance under Dutton is not just uninspiring – it’s historically bad. And while the final judgment will have to wait until election day, the signs already suggest that we are witnessing a campaign that may well become the new benchmark for political failure.

To fairly assess whether this is the worst, it helps to reflect on past campaigns that have gone off the rails. The 2004 Labor campaign under Mark Latham is often cited as one of the most disastrous in living memory – not because it started poorly, but because it collapsed spectacularly in the final week with the announcement of a poorly conceived forestry package in Tasmania, and general perceptions about whether Latham was suitable or ready to become prime minister.

What had been shaping up as a competitive challenge to John Howard ended in humiliation, delivering Labor its worst two-party preferred result since the Great Depression era of 1931. Then there’s John Hewson’s 1993 campaign – the infamous ‘birthday cake’ GST interview that blew up what had been a well-structured campaign until that moment. Hewson’s honesty in attempting to explain the complexities of his tax policy became the very issue that sunk him, crystallising voter anxiety and ridicule in a single media moment.

But in each of these cases, the narrative of collapse hinged on a single major failure – Latham’s handshake gaffe, poor forestry policy and erratic late-stage behaviour; Hewson’s GST stumble, or even H.V. Evatt’s paranoid mismanagement of the Petrov Affair in the 1954 campaign. What sets the current Liberal campaign apart is not one major blunder – it’s the sheer, consistency and relentless accumulation of smaller ones. It started badly, it has worsened each week, and there has been no sign of course correction. It’s a campaign which seems devoid of strategy, vision, or momentum, led by a figure who appears more comfortable delivering apocalyptic soundbites than facing the public with credible policies.

Even among Liberal Party campaigns that were deemed to be poor, some went on to succeed due to external factors. Tony Abbott’s 2010 campaign was scattershot and gaffe-prone, but still nearly toppled a first-term Labor government. Malcolm Turnbull’s 2016 campaign was widely criticised for its lack of energy and clarity but ended in a narrow victory.

Scott Morrison’s 2019 campaign was less a masterclass in politics than a masterclass in luck, bolstered by Labor’s internal missteps and relentless support from News Corporation. What each of these examples share is a degree of chaos – but also a broader media narrative and party apparatus and insiders working overtime to cover for that chaos. Dutton, in contrast, is running a campaign without cohesion nor external cheerleaders. Even the Murdoch press, usually a reliable megaphone for the Coalition, has been lukewarm in its support: there haven’t been any Australia Needs Peter headlines (as there were for Tony Abbott in 2013); he’s not being depicted as the ‘man who saves Australia’, or that Dutton is ‘the answer’.

Dutton also carries baggage that previous Liberal leaders didn’t. Persistent rumours about his past behaviours in the police force, his property wealth, and his temperament have followed him into this campaign, even if they’ve never been substantiated in a way that could stick in a courtroom. But in the court of public opinion, perception always trumps reality. For a political figure to be continually haunted by questions about character – and to never properly address them – is a fatal flaw in any campaign, especially one that hinges so heavily on personal leadership credentials. It’s too late in the campaign to have a real Peter moment, to replicate the attempts by Julia Gillard with her own real Julia moment which she used to resurrect her faltering election campaign in 2010 and, aside from this, the electorate is seeing the real Peter anyway. There is no other persona or vaudeville act that he can switch to: this is it.

And then there’s the issue of political vision. Whatever faults previous opposition campaigns may have had, most at least attempted to present a vision of what government under their leadership might look like. Latham pushed a radical education agenda and a forestry policy that had merit but was poorly conceived; Hewson had economic reform; Evatt had the promise of postwar nation-building (however bungled in the delivery). Dutton’s campaign, by contrast, has offered little beyond fear and resentment. If there is a policy centrepiece, it’s nowhere to be found. If there is an optimistic case for change, it hasn’t been made. The campaign is driven almost entirely by slogans about restoring law and order and fighting ‘wokeness’ – hardly a compelling electoral message for the millions of Australians focused on housing affordability, wages, climate change, and cost-of-living pressures.

Momentum matters – but who’s got it?

As this election campaign heads into its final fortnight, one word is beginning to appear more often: momentum. It’s the intangible force that can carry a party to unexpected victory – or accelerate its descent into a disaster. For the Coalition under Dutton, that force is just not there; the opinion polls are slipping away when they need to be flowing in their favour. After three chaotic and lacklustre weeks, there is no real sense that the Liberal Party has any forward motion at all. And while the Labor Party’s campaign hasn’t exactly electrified the electorate, it has presented itself as steady, competent, disciplined – and – most importantly, in the context of its previous time in office between 2010–13 – not self-destructive.

Momentum in election campaigns is a curious thing: it’s possible to have it and still lose. Labor had it in both 2016 and 2019, where Bill Shorten’s campaign in 2016 closed the gap significantly and gave Malcolm Turnbull a massive fright, and the 2019 campaign generated genuine optimism and an expected victory among progressives – until it all fell apart on the day of election. But the presence of momentum in both cases signalled a party with energy, belief, and a message that at least part of the electorate found compelling. By contrast, a campaign without momentum – especially one mired in negativity and confusion – has never succeeded in winning office, at least not in modern Australian political history.

Anthony Albanese had this momentum in 2022: there was a mood for change in the electorate and he used it to go past a shaky start and lead the Labor Party to a modest but decisive victory. And while the current Labor campaign isn’t bursting with innovation or bold policy reforms, it doesn’t need to be: it just needs to avoid major mistakes and let the Coalition implode under the weight of its own contradictions.

That isn’t to say this is a landslide in the making. This election is taking place in a new political era – one where minor parties and independents have consolidated their place in the national political scene. Over a third of the electorate is expected to vote outside the traditional two-party structure, and while that makes the national vote share more unpredictable, it also supports the strong belief that the Coalition cannot regain government without significant inroads into seats they have lost in recent elections – many of them lost to independents who were elected precisely because of a rejection of Liberal values and behaviour.

While the Liberal and National Coalition was leading in the opinion polls before the election campaign commenced, many observers still believed that it was virtually impossible for the Liberal Party to win a majority in its own right. A pathway to minority government now appears to have been closed off as well. Too many of the electorates the party would need to flip are held by popular independents or are urban progressive seats where the Liberal brand has been damaged – perhaps beyond repair, unless major internal reforms are made. The party hasn’t done the work to rebuild relationships with these communities, let alone articulate why they deserve to govern again.

Of course, in politics, nothing is impossible. A major scandal involving a senior Labor figure in the final weeks of this campaign could change the dynamics but there is no indication that such a scandal is looming. The best the opposition dirt units have managed so far are feeble attempts at character assassination – reheated rumours, personal attacks, or strange claims such as Anthony Albanese’s failure to publicly kiss and acknowledge Tanya Plibersek at the recent Labor campaign launch is a sign of leadership instability. It’s hardly Watergate. If the Coalition is banking on an Albanese disaster to rescue their campaign, they’re not only clutching at straws – they’re showing just how little agency they have left in this race.

It’s also worth revisiting that old political adage: oppositions don’t win elections, governments lose them. And while the Albanese government hasn’t dazzled during this campaign, it hasn’t self-sabotaged either. There is no strong evidence that suggests the public has an insatiable appetite for change, as they did in 2013 and again in 2022. And even if there was, Dutton hasn’t offered any great reasons for the electorate to make a switch over to the Liberal Party.

And that’s the deeper problem for the Coalition. They have failed to generate a momentum for change, and a campaign without momentum becomes a campaign of desperation: errors are made, and it breeds paranoia, stunts, contradictions, and a disassociation from what’s really happening in the campaign. That’s what we’ve seen over the past three weeks. And while the final two weeks is still enough time for surprises, it’s not enough time to reverse the trajectory of a campaign that’s been broken from the start.

So, who has the momentum? On the surface, no one is racing ahead. But politics isn’t just about who’s running – it’s about who’s standing still while others stumble. And right now, Labor is moving forward in all the right ways. The Coalition, meanwhile, is staggering towards the finish line, weighed down by its own inertia. Of course, events can always change, and the unexpected can always arrive quickly from the horizon, when it’s least expected.

And leaders can, all of a sudden, change tact. But Dutton doesn’t appear to be the crazy–brave maverick who can throw caution to the wind, and exploit the new circumstances that might appear after a disruption. He’s just not that sort of leader. Unless something extraordinary happens, the next fortnight will simply confirm what this campaign has already revealed: Dutton’s Liberal–National Party is out of time, out of touch, out of ideas, and out of momentum.

The best campaign I remember was Gough Whitlam's 'It's Time' in 1972, which summed up the national longing for change, for a government which looked forwards, not backwards.

The current situation seems to be the opposite: 'It's NOT Time'. Dutton has failed to present any credible reason for people to want change. Instead, Dutton just wants to go backwards to a past he imagines, but actually wasn't real. And the public isn't buying it. The public wants a competent government which is building a better future, and Albanese is delivering it.

I'm currently straying in Mackellar, where the Independent Dr Sophie Scamps looks set to cruise to victory. This was a safe Liberal seat for a long time, but no longer. The current Liberal Party is no longer liberal - it's conservative. True liberals are not welcome in the Liberal Party, so they have gone elsewhere.

Albanese's long-form interview on 'The Rest is Politics' podcast on Saturday night revealed a leader comfortable with himself and his story and confident he is leading Labor to victory.

The polls confirm Albanese's confidence. As uncommitted people are forced to make a choice in the final two weeks (I'm pre-poll voting this week) I think there is a good chance people who have been watching Trump's chaos in the USA and his threats against other countries, including Australia, will look at Dutton and think, 'No thanks!'.

The polling margin for error of 3% could actually continue to widen, giving Labor a larger two-party preferred margin. A late break could deliver Albanese majority government. Even if that doesn't happen, a Labor-Green coalition could be very successful, just as productive it was under Julia Gillard, which passed more legislation than Morrison.

The trend is for Aussies to reject Dutton's relentless negativity and vote for a confident future under Albanese.