Albanese’s gamble on US tariffs

Australia needs to manage its affairs with independent conviction in the national interest, not subservience to the United States and an unpredictable president.

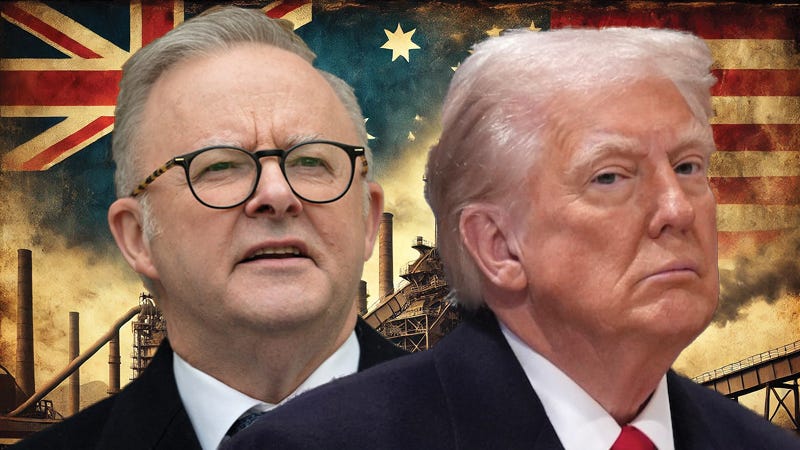

The imposition of a 25 per cent tariff on steel and aluminium imports into the United States has now become a important political issue, not just for the Australian government, but many governments around the world. The recent phone call made by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to President Donald Trump was the start of an attempt to secure exemptions from the tariff, and although the volume of steel and aluminium exports that Australia sends to the United States is relatively small, the political ramifications of being denied an exemption are great. In an election year, Albanese can’t afford to look ineffective when managing Australia’s relationship with the United States, one of its most important strategic and economic partners.

Australia exports around 10 per cent of its overall steel and aluminium to the United States: around $638 million in steel and $275 million in aluminium. While that figure isn’t a dominant share of Australian exports in those sectors, there is a symbolic importance of securing an exemption. Trade with the United States has historically been weighted in favour of the US, a point Albanese emphasised during the phone call to Trump – a relatively unique position given the current US approach to global trade – and in response, Trump described Albanese as a very fine man and acknowledged that the United States has “one of the few” trade surpluses with Australia, but his promise to give Australia’s request “great consideration” remains vague.

The political implications for Albanese are tied to how the Coalition and the mainstream media will interpret a failure to secure an exemption – their responses would be predictably negative – and with a federal election due by May 2025, this is precisely the time when incumbent leaders look to strengthen their standings with policy or diplomatic successes. Failing to secure an agreement would provide fertile ground for his political adversaries, opening the Prime Minister to criticisms that he can’t manage the US–Australia relationship.

There is also the broader challenge posed by the unpredictability of President Trump’s style of governing, if that’s what it can be called. His decisions often appear more reactive than strategic, and seem to arise from immediate calculations of what might be most politically advantageous to him or to his political MAGA base.

The expectation of results based on rules, longstanding alliances, and careful consultation no longer applies under this president, who is willing to announce or retract sweeping economic policies at whim, and this impulsiveness makes negotiating an exemption fraught with uncertainty: one day, an exemption might be promised or hinted at; the next, a change in the President’s mood or priorities could jeopardise that entire arrangement.

Trump’s mindset and the impact on Australia

Trump’s unpredictability – and the purpose behind this unpredictability – remains the main difficulty for any government attempting to navigate these tariffs, not just Australia. The other consideration is that it is not clear if the stated policy goal of bolstering American steel and aluminium production is achievable in a straightforward way – building new or reviving disused smelters in the United States is a long process that might take 12 months or more, during which time shortages could lead to increased prices for American manufacturers. This outcome would contradict Trump’s broader political ambitions for reduced costs and stronger domestic industries, as well as complicating other trade areas, as unpredictability in one policy area could leak into others, potentially prompting more tariffs or retaliatory measures on other products.

From an Australian perspective, the biggest concern is the hit taken by domestic exporters who rely heavily on the United States market. For companies sending the majority of their goods to America, a 25 per cent tariff would make them uncompetitive unless they can quickly find alternative markets. However, as seen in the disrupted trade with China caused by former prime minister Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton in 2020, repositioning to new markets is rarely quick or painless. The complex web of global commerce means exporters need stable, predictable trading environments to manage supply chains and plan for the future. When major partners install sudden barriers, even a moderate drop in export volumes can cascade through entire industries.

Trump’s style also highlights how different he is from his predecessors who, even if controversial in their policies – such as George W. Bush – tended to operate within a more defined framework of institutional checks and long-term strategic thinking. For all of his failings, Bush as least listened to a cross-section of quality advisers and recognised the importance of ongoing alliances. In contrast, Trump’s style is more theatrical and capricious, leveraging unpredictability in an attempt to extract concessions.

Yet this kind of brinkmanship could also backfire: Mexico and Canada have demonstrated that standing firm does not always result in worse terms. Trump ended up settling for essentially the same deals with these countries, loudly declaring victory in an arrangement that scarcely changed from the previous framework. This pattern suggests that Trump thrives on conflict to project strength, even when the outcomes remain unchanged. In practical terms, that means Australia’s best strategy may well be to remain steadfast, continue negotiations, and present a clear-eyed view of the mutual benefits that come from open markets – but also understanding that final decisions could hinge on a whim, an impulse, or a fleeting political calculation by Trump.

All of this makes the current environment precarious for trade partners such as Australia. Just as trade can help maintain positive relationships between countries, it can also become a weapon wielded by leaders who see diplomatic norms as inconveniences that can be easily discarded. While it might be tempting to ignore the theatrics and histrionics of the White House, the potential damage to export industries – and to Prime Minister Albanese’s political standing – can’t be so easily dismissed.

Rethinking Australia’s subservience to the United States

Australia’s deep alignment with the United States has long been anchored in shared post-war interests spanning trade, defence, intelligence, and broader geopolitical objectives. Successive governments in Canberra have reinforced these bonds through significant policy commitments and major defence arrangements, sometimes at substantial financial cost with little direct reciprocal benefit beyond broad declarations of “strong” partnerships and media opportunities for political leaders. Decisions such as the recent AUKUS payment of $US500 million facilitated by Defence Minister Richard Marles show how concessions – and payments – are consistently provided in the hope of preserving good relations and avoiding any appearance of disloyalty. In many ways, this dynamic is reminiscent of the presentation of tributes and gifts to medieval rulers – gold, jewellery or exotic animals – offered more out of obsequious obligation and fear of disfavour than from a balanced negotiation between equals.

The dilemma is not that Australia should seek to jettison its alliance with the United States; the strategic value is clear (somewhat), and there is little appetite to unravel decades of cooperation between the two countries. The question is whether Australian leaders should be more steadfast in articulating national interests, rather than kotowing to the United States. Time and again, Canberra has matched or even surpassed Washington’s requests, whether by allocating funds, supporting military interventions, or echoing foreign policy positions, especially in the Middle East. In return, direct practical benefits have been elusive. This pattern of behaviour suggests that while the alliance’s ideological relationship remains strong – rooted in democratic values and a shared history – a default position of unquestioning support places Australia on the back foot whenever disputes arise.

The example of New Zealand in the 1980s is important in this context, when they were suspended from the ANZUS Treaty over visiting rights for nuclear-powered ships and submarines – in 1984, NZ Prime Minister David Lange enacted legislation to keep New Zealand a nuclear-free zone – and this incident has shown that a smaller country can maintain a strong relationship with the United States and its allies, yet still carve out policies that reflect domestic priorities and strategic judgments.

By acting with a measure of independent resolve, New Zealand managed to reinforce its sovereignty – and national dignity – without irreparably damaging trade or relationships with the United States. Australia could adopt a similar stance, promoting the alliance when it aligns with national objectives but drawing clearer lines when pressured to make concessions of dubious benefit, which is what AUKUS essentially is.

The concern, of course, is that Trump – already known for taking perceived slights personally – might retaliate by imposing or refusing to remove tariffs, just because he doesn’t like Albanese. Or for comments made by Kevin Rudd. Or Scott Morrison. Or for some other spurious reason. Yet that risk is not a permanent condition, and even within the United States, political support for Trump’s combative approach is far from unanimous. Tying national interests too tightly to the impulses of one individual – albeit the President of the United States – can hamper longer-term strategic thinking, especially given the shifting nature of contemporary American politics. A leadership that is consistently ready to meet every whim with acquiescence risks undervaluing its own bargaining position and squandering the chance to negotiate more durable outcomes.

A recalibrated Australian foreign policy doesn’t need to reject a longstanding ally. Instead, it would reflect a clear-eyed understanding that large powers act primarily in their own interests, no matter what type of assurances of friendship are provided. If securing an exemption from the steel and aluminium tariffs becomes purely transactional – as it undoubtedly will be – Australia should feel entitled to drive a harder bargain and this might even earn greater respect in the long term. The reflexive deference currently on display, however, suggests an unbalanced relationship that will continue to exact a price unless Australia chooses to govern its affairs with the same conviction it has often shown in other facets of its global engagement.