Election promises and empty houses: The fiction of fixing Australia’s housing crisis

Changing how a society thinks about housing won’t be easy and we do have to start somewhere. But based on what’s on offer during this election campaign, it’s not going to happen any time soon.

As the 2025 federal election campaign enters its final stages, housing has become the headline issue – and for many good reasons. In most parts of Australia, housing affordability is at crisis levels, home ownership is slipping out of reach for an entire generation, and homelessness is on the rise. With two major parties locked in a battle over who can present the more convincing solution, voters are being bombarded with promises that, on the surface, might sound bold and decisive – but are not much than hollow gestures that are likely to exacerbate the very problems they claim to address.

The Labor Party launched its housing pitch last week with fanfare, led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Housing Minister Clare O’Neil. “More homes and smaller deposits” was Albanese’s main pitch, coupled with a vague assurance that “this isn’t theoretical – this is happening”. O’Neil promised renters a better deal and first-home buyers a smoother path into the market, while emphasising Labor’s plans would improve housing supply.

Meanwhile, Leader of the Opposition Leader, Peter Dutton – not to be outdone – announced a policy designed to “drive up home ownership” by making loan repayments tax deductable and increasing supply and cutting demand through a reduction in Australia’s migration intake, even though it’s not clear how the ‘driving up’ part will actually be achieved. “That’s what we’re on about here, drive up home ownership,” he said, repeating the same phrase with the same emphasis as though saying it twice might make it more coherent and memorable.

But behind the political theatre there’s a reality that’s being ignored – economists across the board have criticised both parties’ plans as economically illiterate and strategically misleading. Despite their superficial differences, the policies from both camps share a common flaw: they fail to confront the structural causes of Australia’s housing crisis, and in some cases, make them even worse.

For decades, Australia’s housing market has been distorted by a series of short-term fixes and politically expedient incentives that ignore the long-term consequences. The First Home Owners Grant, introduced by the Howard government in 2000 with a $7,000 sweetener to help buyers overcome stamp duty costs and the implementation of the GST at the time, is a classic example. Predictably, house prices rose by roughly the same amount, cancelling out any real benefit to buyers and, instead, inflating the market. Those who could already afford a home received the benefits; those just outside the threshold were left further behind. The policy, well-intentioned as it might have been – and that’s stretching credibility and the benefit of doubt as far as possible – misunderstood how markets respond to demand-side subsidies without an equal or greater increase in supply.

In this election, the same flawed logic is being repeated, as it has been over the past 25 years in federal and state politics. Offering financial incentives to buyers – whether through lower deposits or targeted grants – without addressing land availability, construction rates, zoning restrictions, and rental security, just adds fuel to the already massive housing bonfire. Demand increases, prices rise, and affordability declines even further. Real estate agents might be very happy about these outcomes, but for ordinary Australians, they are an ongoing disaster.

Neither party appears ready to challenge the most sacred cows of the housing policy debate, and the most obvious: negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions for investors. These mechanisms have turned housing from a basic human need into a financial investment asset, distorting incentives across the board. Investors are rewarded for snapping up multiple properties, pushing up prices and rents, and competing directly with aspiring homeowners. As long as these tax arrangements remain untouched, boosting the supply-side alone will not change anything – especially when many of the new homes being built are aimed not at low- or middle-income earners, but at the upper end of the market or the speculative investor class.

The housing crisis is not just an issue about economics, but of values. What housing is for? Is it a commodity for accumulating wealth, or a public good that ensures shelter for everyone? If the objective is to get roofs over heads, the solution is straightforward: build more public housing, in urban centres and regional towns. Abandon the failed experiment of privatised solutions and instead fund, manage and maintain government-owned dwellings designed for long-term use, not short-term profit. Certainly, the federal government is building more housing through the Housing Australia Future Fund, but it’s just a drop in the ocean: 40,000 additional dwellings over five years – or an average of three houses in each suburb across Australia – is just not enough.

The policy alternatives do exist – but the political appetite to offer something different is just not there. And in an election campaign where housing headlines win the votes, both Labor and the Liberals seem more interested in appearing to do something, rather than actually solving the problem itself. It’s a competition of nothingness. These policies are carefully crafted illusions – gestures aimed at pacifying public frustration without threatening the structural drivers of the crisis. And for as long as that continues, housing in Australia will remain a privilege for the wealthy and the already-there propertied class, and not a right for the many.

How neoliberalism hijacked Australia’s housing market

To understand why housing in Australia has reached a crisis point in 2025, it’s important to look beyond the soundbites of this year’s federal election campaign and examine how we got here. This housing crisis hasn’t been created through some natural disaster or calamitous economic collapse – it’s through decades of political choices rooted in neoliberal ideology and a systemic redefinition of housing from a basic human necessity into a wealth-generating asset class.

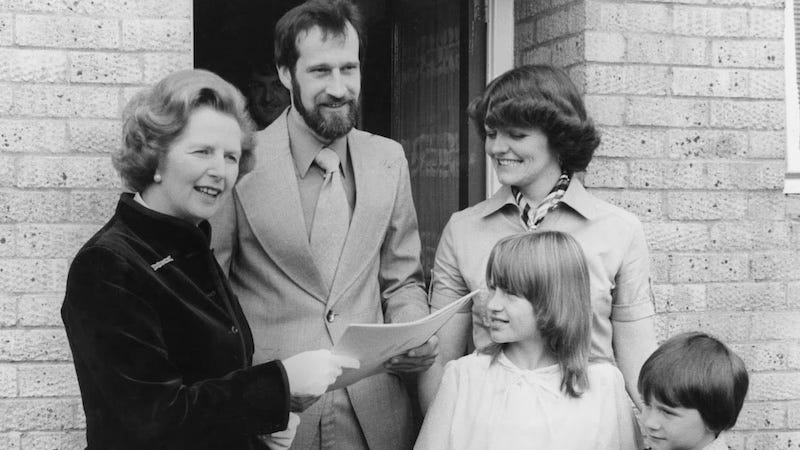

The roots for this go back to the early 1980s with the rise of Thatcherism in the United Kingdom. Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Right to Buy’ policy encouraged public housing tenants to purchase their homes at a discount, reducing the stock of social housing while forcing through a new Hayekian economic and cultural model: private home ownership not just as a right, but as a moral virtue. This ideological shift then appeared in other parts of the world, including to Australia, where successive governments of all persuasions have embraced home ownership as a tool for individual wealth creation and political loyalty.

In Australia, this ideological shift crystallised during the Howard era. In 2000, the Howard government halved the capital gains tax on assets held for more than a year and retained the ability for property investors to negatively gear – meaning they could deduct losses on rental properties from their taxable income. The combination of these two changes made property speculation vastly more attractive, incentivising Australians to invest in their second, third, or even tenth home, and turning ordinary middle-class households into miniature investment firms.

By 2023, over 2.2 million Australians owned investment properties, and 71 per cent of all new property loans went to investors, not first-home buyers. More than 20 per cent of landlords owned multiple investment properties, with some holding portfolios of five or more dwellings. In the same period, only about 30 per cent of new housing stock was accessible to first-time buyers. Meanwhile, public housing stock declined from 6 per cent of total housing in the early 1990s to less than 3 per cent today, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The remaining public housing is concentrated in disadvantaged areas, underfunded, and stigmatised – a major change from its original role as a core pillar of social stability.

This transformation of housing into a speculative asset – one protected and inflated by tax policy – has fueled a self-perpetuating cycle of unaffordability. Every election brings a new round of incentives designed to appear helpful, even if they are not: first-home buyer grants, deposit schemes, shared equity models. But these demand-side policies only serve to increase purchasing power without expanding supply, pushing prices up further and worsening inequality.

The root problem is not just a shortage of houses: it’s the systemic design of a housing economy that favours capital appreciation over shelter. It is the belief that property is a market first and a home second. It is the deliberate political cowardice that refuses to make changes to negative gearing or capital gains tax discounts – despite clear economic evidence that these policies distort the market and force prices up.

The COVID-19 pandemic added complexity to an already volatile system. Population growth paused, construction slowed due to supply chain disruptions and labour shortages, and investors with financial buffers held on while prices continued to rise. But the post-pandemic recovery saw a rapid resurgence in population movement and migration, particularly to regional areas and outer suburbs – just as interest rates rose and inflation began eroding real wages. Renters, particularly low-income earners, have been severely impacted. In 2024, rents in Sydney and Melbourne rose by over 30 per cent, with regional areas such as Ballarat, Sunshine Coast, and Launceston not far behind. Vacancy rates in some cities have fallen below 1 per cent, triggering bidding wars for basic accommodation.

This broken system does not serve tenants or aspiring homeowners: it benefits those who already own multiple properties, enjoy tax subsidies, and can sit on appreciating assets while the rest of the population struggles with unaffordable rents and impossible entry points into the housing market.

Solutions do exist – but they require courage and a willingness to rethink the role of housing in Australian society. One option is to reintroduce public housing at far greater scale – just as governments did in the post-war period in the 1950s and 1960s – not just for the most vulnerable, but as a viable, long-term alternative to private renting or ownership. This could take the form of mixed-income developments, integrated into existing communities, professionally managed, and well-designed.

Secondly, Australia must confront its tax policy distortions head-on. Negative gearing should be phased out or restricted to new builds, while capital gains tax discounts should be wound back, particularly for short-term speculative sales. This would not only curb demand from investors, but also begin to restore fairness to a system that heavily favours wealth over work.

Third, tenancy law reform is essential. The fear that stronger tenant rights will destroy the investment market is misplaced – in reality, long-term tenants who treat homes with care are a better prospect than frequent turnover, rent arrears, and vacancy losses. Germany’s housing system, which emphasises stable long-term renting and discourages speculation, offers a different model that is worth studying.

And finally, short-term rental platforms like Airbnb and Stayz must be regulated. Entire homes listed as perpetual short stays reduce long-term supply, inflate local housing markets, and hollow out neighbourhoods. Cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin and Barcelona have introduced caps, taxation, or outright bans on such practices, and Australia must follow suit before tourist pressure further cannibalises the rental stock.

The housing crisis in Australia is not just a matter of economics – it’s a symptom of a deeper social and political failure. It reflects the dominance of neoliberal thinking, where everything is commodified, even the roof over one’s head. Until we reclaim housing as a public good, treat it as infrastructure, and design policies that serve people rather than profits, the crisis will continue – no matter which party is in power or how many new grants they offer in the lead-up to election day.

The long road back: Reclaiming the soul of housing

If Australia is ever to overcome this housing crisis, it will take more than policy tweaks and political promises – it will require a deep and deliberate shift in mindset. The psychology of home ownership in this country has been fundamentally transformed over the past 25 years, where a home is less likely to be viewed as a place to live, raise a family, and contribute to a community. Instead, it has become an investment vehicle, a tool for wealth accumulation, a line item in a portfolio. To address the crisis in any meaningful way, this commodified view of housing must be reimagined – and that process could take a generation.

Today, this mindset on property as an investment is embedded not only in the financial system but in the culture itself. Home ownership is presented as the pinnacle of financial success – there isn’t anything inherently wrong with owning or wanting to own a home, but it’s not the only way to live or contribute to the world. Those without property ownership are seen as transient, unstable, or financially imprudent – or just renting – despite working full-time jobs, paying exorbitant rents, and often being better budgeters than those who hold multiple properties. Young people are encouraged to ‘get into the market’ as early as possible, as though they’re investing in stocks, not securing a basic human need.

But reversing this deeply ingrained psychology won’t be quick. Just as it has taken 25 years to arrive at this distorted reality, it could take another 25 years to undo it, and that’s assuming that we begin the process now – which we are clearly not. Every year the issue is kicked further down the road; every election brings new demand-side incentives that reinforce the housing-as-commodity type of thinking.

Every parliamentary debate on housing reform is clouded by the personal interests of MPs and senators who own multiple investment properties. As of 2024, nearly half of federal parliamentarians owned at least one investment property, a clear conflict of interest that undermines any attempt at genuine reform.

This concentration of property ownership among lawmakers and political donors creates a structural bias in favour of the status quo. Who among them would willingly legislate themselves into a lower net worth? And yet that’s exactly what true reform would require: measures that reduce speculative investment, that lower housing returns, and that reset the housing economy in favour of liveable future, not profit.

This is not to say people shouldn’t be able to build wealth or plan for their futures – but we need to ask at what cost. When the housing aspirations and simple living of millions are diminished to maintain the capital gains of a few, we are no longer a fair society. A home must be seen first as shelter, then as security, and only then – if at all – as an asset.

Changing how a society thinks about housing won’t be easy but we have to start somewhere. It will require political courage, sustained advocacy, and new forms of narratives about housing and living as a citizen in a community. The sooner we begin, the sooner we’ll reach the future that we claim we all want: an Australia where a home is something you live in, not something you hoard.

Spot on analysis. Negative gearing and capital gains concessions do need to go to remove one of the barriers to more widespread home ownership. There are at least two other neoliberal objectives that should be addressed.

Firstly, the structural shift to part time work/holding down 2-3 jobs, contracting in the gig economy. I was studying for an MBA in 2000 and already the proposition was being taught/learned that temporary work is the way of the future. Half the class disagreed - yet here we are.

Secondly, along with the changed nature of employment came the depression of wage increases in line with CPI (at least), while corporate profits increased (generally, ok my super is doing well) and ludicrous rise of executive remuneration. So it is that many more times annual income to buy a house now then 30-50 years ago.

There may be a third area that I mention from experience. It has to do with land planning and how the developers develop the land and release it for sale. Two of many points:

Better regulation of land planning and development. I helped my son buy a 300m2 block of land in north west Sydney back in 2020. From memory and by way of example the price of the always limited releases of about 20 blocks each time were: mid 2019 ~$320k (when we started looking ); late 2019 ~$360k; early 2020 ~$430k; late 2020 $460k - when we bought. As my second son wanted to buy we started looking in late 2021 ~$580k; late 2022 $650k - when we gave up. Blocks of land of 240m2 in that area are now going for $750 to $850k. I have not heard one valid explanation of this rate of increase. Demand in some way is obviously one, but so too is greed.

Complete development of a block. Developers nowadays seem to do the basics level block, retaining wall, drainage and then roads etc. However my sons block cost another $100k to put in more drainage, level it to a building standard, added to the retaining wall and other bits and pieces that should ideally be done by the developer. So The $100k would generally be unbudgeted for a new home buyer and it gets added to the price of the house later when it is sold.

Superb piece. Now all we need is for politicians to gain some courage and conviction to do what must be done.