Fuck the colony: The uncomfortable truths about colonisation

Australia will not move forward until it is willing to listen to Indigenous people – not just the ones who speak softly, but also the ones who, like Lidia Thorpe, refuse to be silenced.

The recent royal visit to Australia was yet another reminder of the nation’s ambiguous and often contradictory relationship with the British monarchy. In what has become a predictable spectacle, political leaders and mainstream media alike rolled out the red carpet for King Charles III and Queen Camilla, who were met with the usual fanfare, despite a weak public response.

The political and media establishment, once again, abandoned any semblance of critical faculties, indulging in obsequious behaviour that has come to define these visits. The tour was filled with the obligatory orchestrated public relations opportunities – photo-ops with community leaders, sheepdogs, parrots, alpacas, and brunches with recycled supermarket salads. However, the real significance of the visit only emerged when Senator Lidia Thorpe delivered a raw and unapologetic critique of the monarchy’s legacy in Australia.

“This is not your country. You committed genocide against our people. Give us our land back. Give us what you stole from us – our bones, our skulls, our babies, our people. You destroyed our land. Give us a treaty. We want a treaty in this country. You are a genocidalist. This is not your land. You are not my king. You are not our king. Fuck the colony.”

Senator Thorpe’s fiery speech was a contrast to the carefully curated optics of the royal tour. She directly addressed King Charles, accusing him and his forebears of committing genocide against Indigenous Australians and demanded the return of stolen land, bones, and lives – direct, emotional, and unapologetic, a bold departure from the polite deference that usually surrounds royal visits, the Senator’s outburst sparked outrage among conservative MPs and monarchists, with calls for her resignation.

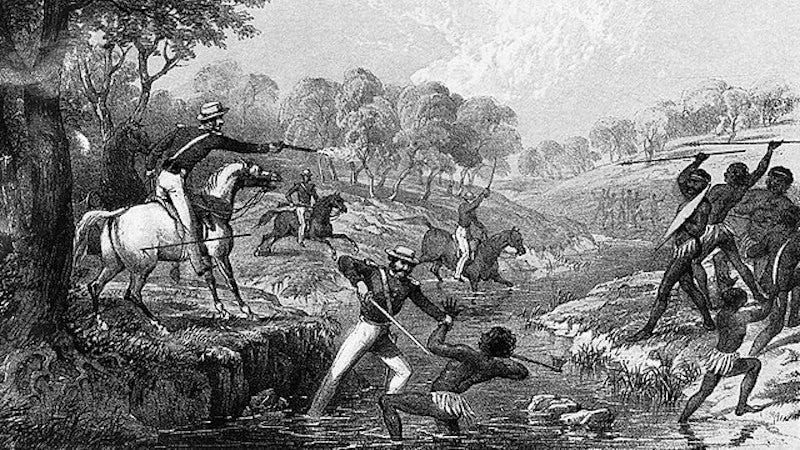

However, what Thorpe said was historically correct: British colonisation in Australia did lead to the displacement, exploitation, and systemic eradication of Indigenous peoples. Yet, instead of confronting this uncomfortable truth, the political right focused its energy on condemning the messenger rather than addressing the message.

Her comments also reflected a broader reckoning with the monarchy’s place in modern Australia. While King Charles has inherited the crown, the scars left by British colonialism are far from healed. The concept of terra nullius, which declared Australia an uninhabited land ripe for British settlement, legitimised the theft of Indigenous lands and cultures. There has never been a treaty between the Indigenous peoples and the British or Australian governments, leaving a significant gap in the nation’s history and its attempts at reconciliation. If King Charles genuinely wanted to contribute to Australia, he could acknowledge this dark history and support a meaningful process toward reconciliation, including the negotiation of a treaty. Instead, the tour was little more than a ceremonial exercise, disconnected from the pressing realities of Indigenous justice.

The royal visit achieved little more than superficial pageantry. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s interactions with the King, while diplomatically necessary, carried an air of discomfort – an awkward balancing act between respect for the head of state and the growing republican sentiment in the country. It was a far cry from the dignified yet clear republican stance that former leaders like Paul Keating and Bob Hawke managed to strike. King Charles’ diminishing popularity, coupled with a lack of meaningful engagement with Australia’s political and cultural challenges, left many questioning the necessity of the visit in the first place. While the media tried to paint a picture of royal success, the reality on the ground suggested otherwise: a monarchy increasingly out of touch with the modern Australian ethos.

Ultimately, Senator Thorpe’s speech may have been the most memorable part of the royal tour – not so much for its shock value, but for the uncomfortable truths it laid bare. The British crown’s historical and ongoing relationship with Indigenous Australia is fraught with injustice, and the royal family’s unwillingness to acknowledge or address this legacy only deepens the divide. While the political and media establishment may continue to treat the monarchy with reverence, the public’s growing disinterest, combined with the resurgence of republican debate, suggests that the royal family’s days as Australia’s head of state are numbered.

The focus on polite decorum instead of the damage of colonisation

Following Senator Thorpe’s public outburst, a chorus of conservative MPs quickly brandished constitutional rhetoric to support their calls for her resignation from Parliament. Most notably, Senator Bridget McKenzie, infamous for her involvement in the sportsrorts affair, positioned herself as an authority on constitutional matters, claiming that Thorpe had breached her oath of allegiance and – delivered without any sense of irony – she must therefore face consequences!

This assertion was not only legally unsound but also revealed the shallow understanding many of these MPs have of Australia’s Constitution. McKenzie’s response, much like others from her conservative counterparts, centred on Thorpe’s perceived breach of decorum, rather than addressing the substance of Thorpe’s critique.

McKenzie’s claim that Thorpe had violated her oath of allegiance by disavowing the King betrays a misunderstanding of constitutional principles. The oath of allegiance, which all parliamentarians swear upon taking office, binds them to serve the interests of the Crown according to the law, but it does not preclude them from criticising the institution or advocating for political change. In fact, the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech, even for parliamentarians expressing dissent against the monarchy. Thorpe’s declaration that Charles is not my king may have been inflammatory to some, but it was well within her constitutional rights. The calls for her resignation reflected not a misunderstanding of law, but an ideological disagreement that conservative figures chose to frame as a constitutional crisis.

What was lost in this conservative uproar was the essence of Thorpe’s message. Instead of engaging with these critical issues, conservative MPs such as McKenzie fixated on her tone and choice of words, and deflected from this reality by appealing to “respectability politics”, choosing to attack Thorpe’s “manners” rather than confront the brutal truth of colonisation.

The notion that the King has “earned our respect,” as some conservatives argued, is also dubious at best. King Charles III’s ascent to the throne was a matter of birthright, not merit. He has neither been a towering figure of moral authority nor a leader of significant social change. His refusal to meet with Senator Thorpe, an elected representative seeking dialogue on critical historical injustices, speaks volumes about the monarchy’s disconnection from the issues that matter to many Australians. Thorpe’s frustration, far from being an act of bad manners, was a reflection of the deep-seated anger and pain felt by Indigenous Australians who have been historically ignored and sidelined by the institutions of power.

A treaty has long been a critical issue for First Nations Australians, and it would represent not only a recognition of Indigenous sovereignty but also a step towards reconciliation and justice. The British Empire’s legacy in Australia, marked by the theft of land, the destruction of cultures, and the systematic genocide of Indigenous peoples, remains a wound that has never fully healed.

In this context, the conservative backlash against Thorpe’s speech was not just about protecting the monarchy – it was about preserving the status quo. The insistence on decorum over justice, on manners over truth, reveals a deeper discomfort with confronting the violent history of colonisation and the demands for accountability that come with it.

Radical voices in Australian politics, both on the left and the right, have long used provocative language to push their agendas. Pauline Hanson, for example, has made a career out of inflammatory rhetoric, yet her place in Parliament has never been threatened by the same conservative voices now calling for Thorpe’s removal. This double standard is telling – when a radical figure from the right engages in polarising speech, they are often defended as a representative of free speech. But when a Black Indigenous woman speaks truth to power, she is met with demands for her resignation.

In many ways, the outrage surrounding Thorpe’s speech is less about her actual words and more about the discomfort they caused. Thorpe’s refusal to adhere to the expected norms of civility in the presence of royalty may have offended conservative sensibilities, but it brought much-needed attention to the issues of colonisation, Indigenous justice, and the role of the monarchy in modern Australia.

A call for justice silenced by Australia’s political and media elite

With nearly a million Indigenous people in Australia, there is, of course, a diversity of opinions within the community about the path toward justice, recognition, and reconciliation. Not every Indigenous person will agree with Thorpe’s methods or rhetoric, but her powerful outburst likely resonated with many who share her frustration at the slow pace of change.

Thorpe’s speech, now being referred to as the Not My King moment, could well be seen as a modern counterpart to Paul Keating’s historic Redfern Speech in 1992. While Keating’s speech was delivered with measured statesmanship, Thorpe’s was raw, unfiltered, and deeply personal. Yet, both speeches share a common theme: the urgent need for Australia to reckon with its colonial past and the ongoing oppression of its Indigenous peoples. Thorpe’s speech, while brief, spoke to the heart of Australia’s unresolved history of dispossession and genocide.

The backlash Thorpe faced, especially from white conservative figures, was both predictable and telling. Her critique of the monarchy and call for a treaty were met with the same dismissive reactions that have historically been used to silence Indigenous voices. As Thorpe herself noted, the colonial system in Australia has a long track record of shutting down Black women who dare to speak out against injustice. The immediate focus on her tone, rather than the substance of her critique, is emblematic of a broader pattern in Australian society – when Indigenous people speak out about their oppression, particularly in ways that challenge the comfort of white Australia, they are met with derision, hostility, or attempts to silence them altogether.

The recurring symbolism in Australian politics – telling Indigenous people to sit down, shut up, and accept whatever limited gestures of recognition are offered – has been a persistent barrier to progress. We saw it with Adam Goodes, a proud Indigenous footballer whose outspoken stance against racism was met with vicious booing and media condemnation. And we see it again with Thorpe, whose uncompromising stance has been met with calls for her to be silenced, removed from Parliament, and dismissed as a radical. It’s a pattern that has played out time and time again: when Indigenous people speak out, particularly in ways that make white Australia uncomfortable, the response is to shout them down, not to engage with the substance of their critique.

The scene of King Charles and Prime Minister laughing together in the aftermath of Thorpe’s outburst also reinforced this dynamic. To them, it may have been a momentary disturbance – an irritation to be smoothed over before returning to the pleasantries of royal protocol. But to many watching, it was a symbol of how the political and cultural establishment in Australia continues to dismiss Indigenous voices. As Prime Minister, Albanese could have used the moment to engage with the issue of a treaty, to ask the King what role the monarchy might play in addressing the injustices of colonisation. Instead, the moment passed in a smug exchange, with no acknowledgment of the real, painful history that underpins Thorpe’s anger.

When Indigenous people express their views in ways that align with the expectations of white Australia – calm, conciliatory, and deferential – they are tolerated. But when they speak with passion, anger, and truth, as Thorpe did, they are vilified and shut down. This is not a new phenomenon; it has been the default response to Indigenous activism for decades. Yet, this unwillingness to engage with the harder truths of Australia’s colonial past and present is precisely what holds the nation back from genuine reconciliation.

Thorpe’s speech may have been radical, but it was not wrong. Her words reflected the frustration and anger of many Indigenous Australians who are tired of being told to wait, to compromise, and to accept symbolic gestures in place of real justice. As long as the establishment continues to silence those voices and avoid the difficult conversations, the wounds of Australia’s colonial past will remain unhealed. The country will not move forward until it is willing to listen to Indigenous people – not just the ones who speak softly, but also the ones who, like Lidia Thorpe, refuse to be silenced.

Absolutely! I'm sick of double standard by the Right on free speech:) I think also there's the fundamental recognition that, even if you disagree with specifics of what Thorpe was saying, ultimately her words come from a place of goodwill and the desire to make the world a better place, a desire for justice. By way of contrast, conservative extreme speech always comes from a place of hatred, selfishness and a desire to hold on to the old state of the world, no matter how much injustice it contains:)