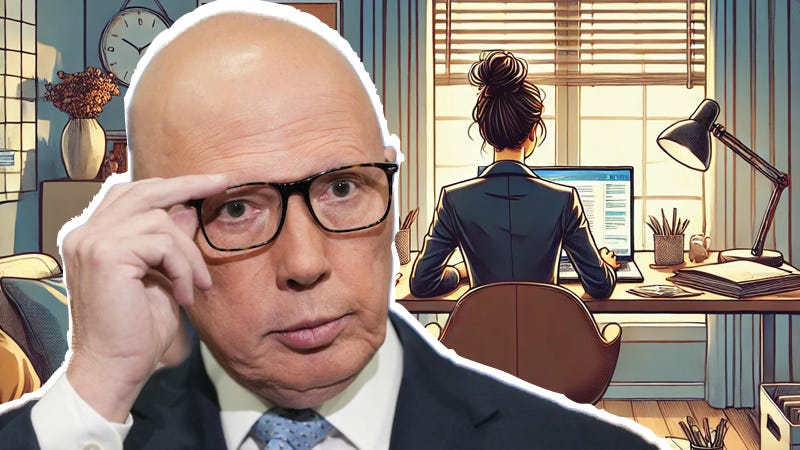

How Dutton’s campaign fell apart

The second week of the election campaign has seen the opposition leader’s campaign disintegrate and a Prime Minister unwilling to talk about climate change.

The second week of the federal election campaign – a stage when political parties are seeking stability – descended into yet more misfires for the Liberal Party, and it started off with bringing one of the worst deals in recent political history into the campaign: the lease of the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company, the Landbridge Group. Despite having implemented the entire deal, the Coalition sought to reframe the issue as a national security threat in an attempt to reignite anti-China sentiment and regain some control over their campaign.

Peter Dutton was scheduled to announce the cancellation of the lease as part of this scare campaign, but the move backfired spectacularly. Labor – tipped off directly by the Liberal Party itself – pre-empted the announcement with Anthony Albanese revealing a near-identical policy the day before. It wasn’t just a political embarrassment – it completely nullified the issue. What was meant to be a moment of nationalistic megaphoning for the Coalition became an echo of the government’s position, with Dutton left to agree with a plan that had been in the public domain for less than 24 hours. Worse still, the very issue the Coalition had tried to weaponise, reminded voters that they were the ones who had signed off on this poor deal in the first place.

The Coalition’s attempt to magnify this into yet another chapter from their now-familiar China scare campaign exposed the big contradiction at the heart of their message: how can a nation’s largest trading partner also be its greatest security threat? It’s not an existential question – if China really is that threatening, why sell or lease major infrastructure to Chinese companies in the first place?

This focus on the Port of Darwin wasn’t just about national infrastructure or foreign policy. It was about the cynical recycling of fear for political gain – and this time, it didn’t work. Labor outflanked them – ironically, with the direct help of a leak from some unhappy people within the Liberal Party – the media saw through the tactic, and voters were reminded once again that the greatest national security threat of all is the political cowardice that always arrives wrapped in a healthy dose of hypocrisy.

The Liberal Party’s civil war

This party leak to the Labor Party, didn’t come from an external source or was accidently found in a discarded filing cabinet on the outskirts of Canberra. It came directly from within, and all signs point to the New South Wales division of the party as the saboteur. It’s the result of a long-standing power struggle between the more ideologically conservative Liberal–National Party of Queensland – Dutton’s base – and the moderates of New South Wales, who would prefer to see their own ascendancy after an election defeat, even if that means handing Labor the win.

It’s not a new dynamic in Australian politics, but rarely has it played out so obviously in the middle of a federal campaign. Behind the scenes, the NSW division, hardly a pinnacle of liberal moderation itself, is increasingly preparing the ground for an Angus Taylor leadership in the event of a Coalition loss. For them, losing in 2025 is an acceptable price to pay for retaking control of the party, silencing the Queensland-led hard-right, and charting a new direction that could win in 2028. If Dutton were to lose his own seat of Dickson in the process – which is a strong possibility – that would be an added benefit.

And while it might seem counterintuitive to sabotage your own campaign, political operatives often view factional victory within the party as more important than electoral success – especially when the electoral odds are already looking grim. The Labor Party also has a strong tendency to do this – the experts! – although it greatest act of factional bastardry would have to be the period between 2010–13, when it destroyed itself during the Rudd–Gillard–Rudd years, and handed the Liberal Party a nine-year period of government on a plate.

Dutton is clearly aware of this internal bleeding. His recent complaints about “elites within the Liberal Party” weren’t random grievances – they were directed at the very people who are undermining him. Yet this public airing of these internal grievances has done little to stop the quiet campaign against him. The NSW division isn’t without its problems: its leadership is fragmented, its ideological direction is confused, and while it’s not the far-right circus that the Victorian branch has become – now home to Christian nationalists and conspiracy theorists – it still harbours its own internal instability.

A mid-campaign policy dump

To add to his terrible week, Dutton’s abrupt abandonment of the Coalition’s plan to force public servants back into the office full-time was less a policy correction than a public confession of political incompetence. In a rare display of a campaign apology, Dutton openly admitted the policy was a mistake, and tried to frame it as a case of miscommunication – blaming Labor for twisting the message, as though the policy hadn’t already collapsed under its own contradictions. In reality, this was not a complex or nuanced idea misrepresented by opponents – it was a shambles from the beginning. Announced with great fanfare to appeal to a supposed silent majority of tradies and working-class voters tired of ‘lazy’ remote workers, it quickly unravelled under the weight of its own impracticality, potential illegality, and hypocrisy.

The sudden backflip didn’t just happen because the policy was debated, articulated over time and then found wanting: it happened because voters hated it. It alienated not only the public servants it directly targeted, but also their families, colleagues, and entire segments of the electorate who had come to see remote work as an essential part of modern life. The Coalition’s attempt to pit ‘real workers’ against ‘keyboard loafers’ collapsed when it became clear that many of those ‘real workers’ were relying on the flexibility of their partners, family members, or housemates working from home.

This flip-flop has confirmed what has been already suspected: the Coalition’s policy platform had been hastily put together, poorly vetted, and driven more by political messaging than any real belief in this platform. Dumping the work-from-home policy in the middle of a campaign sends a message to the electorate – not that the party is being responsive to public sentiment, but that it was unprepared. And worse still, it gave Labor and independents a line of attack that will endure for the rest of the campaign: if the Coalition is already disowning its own policies, how can voters trust anything else they promise?

Ultimately, this isn’t just about one failed idea. It raises a broader question about the Coalition’s readiness for government. What other policies haven’t been tested? What else might collapse under scrutiny? Nuclear energy? Education reform? Taxation? There’s a growing sense that the Coalition, out of government for only three years, hasn’t done the hard policy work in opposition and is only relying on outdated ideas and cynical stunts. And that might be the most damning conclusion of all: a party that once could win by simply showing up, now faces a political world that demands a great deal more – and hasn’t got much to offer.

Leadership in the age of talking points

The first leadership debate of the federal election campaign came and went with barely a ripple, a tightly managed exercise in message control more than any genuine contest of ideas. Albanese and Dutton stood before a studio audience of 100 ‘undecided’ voters and delivered performances that were technically competent but left no lasting impression, with each sticking to their pre-packaged talking points. Albanese rattled off economic achievements, Dutton leaned into cost-of-living anxieties, and the entire event felt like a well-rehearsed dress rehearsal for a show no one particularly wanted to see.

While Albanese won the debate with 44 per cent, to Dutton’s 35 per cent – 21 per cent were still undecided – there was no real persuasion, no momentum gained. It was just another night in a campaign going through the motions.

But the problem runs deeper than just an uninspiring debate. It’s what these debates have become – tightly managed performances with no spontaneity, no improvisation, and no real test of leadership under pressure. They’re relics of a past political culture that demanded less but offered more, where decades ago, political leaders faced unruly, unpredictable crowds and had to sink or swim in real time. Today’s debates are risk-managed into irrelevance.

It’s hard to imagine either Albanese or Dutton confronting a crowd not handpicked by a research firm, let alone dealing with hecklers or winning over a room determined to dislike them. The oratory that once defined great Australian leaders has been replaced by scriptwriters and communications consultants. Politics now happens within the safe walls of subscription media and strategic messaging, not out in the open, where views are tested and leaders either rise or fall on the strength of their character. The electorate deserves to see leaders tested in a way that isn't choreographed within an inch of its life. The current format teaches us nothing and challenges no one.

Two more of these debates are scheduled before election day. They will come and go, and one leader will probably win the polls on the night, but as history shows, it doesn’t matter: Labor leaders have won every election debate since the 2010 election – in most cases, comprehensively – but only Albanese has gone on to win government. What really matters is what happens beyond the studio – on doorsteps, in workplaces, and at the polling booths. But still, these debates continue, more out of tradition than necessity.

There is a perception that the leaders who try not to attend these debates are avoiding scrutiny and are running away from the public, but even when they do show up, it still feels like they are avoiding scrutiny, even if they are physically present.

And so, we’re left with debates that confirm, rather than challenge. They confirm the instinct of many Australians that their leaders don’t really say anything anymore. They confirm that politics has become more about avoiding damage than taking risks. And they confirm that, in a campaign where leadership is supposedly at stake, neither contender wants to be caught off guard. But the real tragedy is that without risk, there is no inspiration – and without inspiration, there is no leadership worth following.

Footballs and fossil fuels

Every election campaign has its unscripted moments, and these unexpected incidents reveal more about a leader’s temperament and values than any carefully rehearsed debate or media conference. This week, two such moments stood out, small but significant in their symbolism. The first involved Dutton, a football, and a cameraman; the other saw Albanese confronted by a climate change activist. Neither moment will decide the election, but the respective reactions say a lot about the politics they represent.

At a photo-op on a football field, Dutton managed to kick a ball directly into the head of a cameraman, Ghaith Nadir. Accidents do happen, but Nadir was an Iraqi refugee and asylum seeker, the very type of person Dutton has spent much of his political career vilifying and targeting with punitive policies and rhetoric. That alone gave the incident a clear subtext, but it was Dutton’s response that turned a simple mishap into something more sinister.

Instead of showing concern or even mild embarrassment, Dutton shouted out that he “got him!”, and then made a joke about the cameraman not catching the ball, laughed it off, and suggested that had it been Albanese, he would have ‘lied’ about the whole incident. It was an oddly triumphant, almost gleeful reaction to an accident that left a man with a head injury, revealing a man more comfortable deflecting with ridicule than showing empathy.

It’s hard to shake the feeling that these moments aren’t just gaffes – they’re brief insights of the leadership style on offer. Where empathy should appear, we see sarcasm. Where humility might have made an impression, we see bravado.

On the other side of the campaign trail, Albanese was confronted by a climate change protester, Alexa Stuart, furious about the government’s continued approval of new coal and gas projects. She accused the Prime Minister of condemning her generation to a future of climate catastrophe, and she had every right to be angry: despite all the rhetoric about net zero and clean energy, Labor has green-lit 173 new fracking wells in Queensland and continues to approve existing fossil fuel projects under the fiction that they are not ‘new’ developments, but ‘expansions’. But a bigger gas field is still a bigger gas field, and a deeper coal mine still burns more coal.

Albanese’s response was to brush it off. He refused to comment, claiming that engaging would only encourage more protesters. But this isn’t a time to be avoiding engagement. Elections are one of the few moments when political pressure has real leverage – when leaders can be held to account by the very people they claim to represent. Protest during a campaign isn’t a disruption; it’s a democratic necessity. These aren’t just votes at stake – they’re lives, futures, and the shape of the planet to come. The climate crisis isn’t going to pause for polling day.

These two incidents – one flippant, one furious – reflect deeper fractures in the political landscape. Dutton’s football blunder became a metaphor for his political instinct to punch down and dismiss criticism with derision. Albanese’s evasion of a powerful challenge from a young activist highlighter the contradiction between his party’s climate narrative and its actions. But at the least, both moments broke through the campaign veneer. And in a race already marked by strategic missteps and clichéd performances, it’s these raw flashes of character that voters might remember most.

Dutton appears not to have done the hard work required to produce well-planned policies. Instead he relies on expensive, half-baked thought bubbles like nuclear power and recycling bad ideas from the past like temporarily cutting the fuel excise, which undermines the budget and increases government debt.

The Morrison Government inherited about $260b in government debt and more than doubled it in 9 years, undermining the Liberals' claims of competence.

The Albanese government has restrained government debt while managing two budget surpluses, proving it is financially more responsible than the Liberals.

Even Dutton's one fresh idea to temporarily make home loan interest tax deductible for first home buyers won't increase the number of houses built, since the houses will have already been built before the tax deduction can be claimed.

Albanese's 5% deposit scheme will help more people get into their first home, since it will help them to raise the deposit to sign the home contract.

Only Albanese is proposing to build more social housing for renters, which will reduce homelessness.

Dutton wants to reduce Albanese's plan for 1.2 million new homes to only 600,000, a really bad idea.

Albanese has allowed more coal and gas mines, but that is more than offset by his major push to lift renewable power to 90% by the 2030s.

Dutton would undermine renewable power for a hugely expensive, wasteful, nuclear fantasy.

This election is a contrast between a competent, successful, moderate Albanese Government and an incompetent Dutton Opposition which wants our progress to stagnate.

Trump has made the world a more dangerous place, so we need the current government's competence to avoid disaster.

Technically - at least within the terms of conventional economics - Albanese has lead a reasonably effective government, against wall-to-wall idiocy from the Coalition. It would be almost impossible to lose such a comparison.

And that's probably how history will judge Albanese and this government: disappointing, but less bad than the alternative rubbish.

Given what Australian politics has devolved into over the last decade or so, the real political contest should be (and may yet come to be) between Labor and the Greens - which would be much more like the old and more meaningful contest between Labor and Liberal, back when the name was a less inaccurate description of the actual content.