Navigating Islamophobia in Australian media and politics

The evolution of this media–political landscape will be crucial in shaping more inclusive and effective governance.

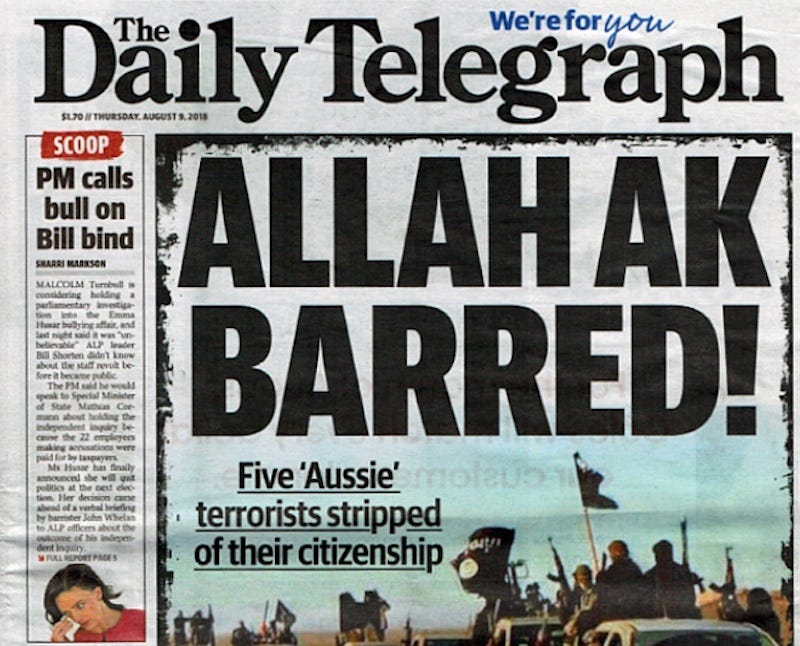

The narrative surrounding multiculturalism and media representation in Australia presents a complex and often contradictory narrative. The recent remarks by the Leader of the Opposition, Peter Dutton, exemplify a troubling pattern where political rhetoric not only reflects but exacerbates societal biases. Dutton’s comments, which linked the prospect of a minority government with the inclusion of Muslim candidates from Western Sydney, implicitly cast these potential representatives as threats to political stability, in his words, “a disaster”. Such statements are not isolated incidents but are part of a broader narrative that often surfaces in Australian political discourse.

The recent resignation of Senator Fatima Payman from the Labor Party to sit as an independent further fueled the media’s engagement with themes of race and religion. Payman, a refugee from Afghanistan – and visibly Muslim – has been at the centre of what can be described as a media spectacle, with her actions and statements scrutinised and interpreted through a lens of racial and religious stereotypes. The coverage by various media outlets, from Seven West Media, the ABC and through to News Corporation, has varied in tone, but a common undercurrent of skepticism and fearmongering about Islam and its adherents persists.

Commentary provided by figures such as Andrew Bolt – who breached the Racial Discrimination Act for publishing racist material in 2009 – claiming that with Payman’s shift, “Australian politics just got more dangerous”, illustrates how media figures can influence public perception by perpetuating narratives of fear and otherness. Bolt’s derogatory remarks about Muslim victimhood and his targeting of Payman’s background as a refugee highlights a broader media trend that often borders on – and surpasses – Islamophobia. Such narratives not only distort public discourse but also reinforce societal divisions by emphasising differences rather than commonalities.

This media portrayal does not exist in a vacuum. It interacts with and shapes the political landscape, where the fear of the ‘other’ can be a powerful tool in mobilising electoral support. The political utility of Islamophobia, as seen through the actions and words of some Australian politicians, raises questions about the role of media in either challenging or perpetuating these divisive strategies. While there are exceptions, such as the efforts of broadcasters like SBS to present a more nuanced and diverse perspective, the dominant media narrative tends to favour a portrayal of Australian society that prioritises Anglo-centric views and marginalises minority voices.

The presence in the media of figures such as Waleed Aly, Stan Grant, and Fauziah Ibrahim does offer alternative viewpoints, yet they often face a paradox. While their perspectives are crucial in fostering a more inclusive dialogue, their acceptance and success are contingent upon aligning with a predominantly conservative mainstream narrative. In Grant’s case, when he strayed away from this narrative and offered his perspectives as an Indigenous Australian, he was severely criticised and ushered out of the media industry.

This dynamic illustrates the challenges faced by minority voices in gaining traction within a media landscape that is predominantly Anglo, male, and oriented towards centre-right political narratives.

Media representations and political rhetoric in Australia reveals a landscape fraught with challenges for minority communities, particularly for Muslims and especially since the events of 9/11 in the United States in 2001. The narrative not only reflects existing societal biases but also has the potential to shape political and social outcomes. Understanding and addressing these dynamics is crucial for moving towards a truly inclusive and representative Australian society.

The struggle for secularism and diversity in Australian parliament

As Australia manages the ideals of multiculturalism and secularism, the practices within its political institutions reveal a continuing struggle to reconcile tradition with a diverse and changing demographic landscape. The recitation of the Lord’s Prayer to commence Parliament – reintroduced by the Howard government in 1996 – symbolises this tension. This ritual, ostensibly benign and reflective of moral aspirations, inadvertently highlights the incongruence between Australia’s secular commitments and its ceremonial practices, marginalising non-Christian parliamentarians and, by extension, the diverse populace they represent.

The use of the Lord’s Prayer as a parliamentary opener is more than just a formality; it is a symbolic act that highlights the perceived primacy of Christian values at the core of governmental proceedings, alienating members of other faiths and those with no religious affiliation. It also highlights how deeply embedded and normalised Christian norms are within the structures of Australian governance, despite the nation’s secular policy and diverse religious landscape.

The representation in Parliament, although becoming more diverse, still lags behind the actual demographic makeup of Australia. The 2022 federal election brought in more representatives from various backgrounds, yet the political and cultural infrastructure has been slow to adapt. This sluggishness in embracing true diversity is further compounded by the media and political narratives that often view non-Christian participation, particularly Islamic, with suspicion and as a potential threat rather than a reflection of societal diversity.

The historical context of Australia’s foundation as a secular nation, highlighted by the Australia Act of 1986, provides a constitutional backing for broader religious freedom and representation. The legacy of figures such as Alfred Deakin at the time of Federation in 1901 and his engagement with spiritualism and theosophy highlight the varied spiritual undercurrents that have shaped Australian public life, which are often overshadowed by the dominant Christian narrative.

The discussion around whether to remove the practice of reciting the Lord’s Prayer in Parliament is not only about a procedural detail; it is emblematic of a larger debate about what values Australia wants to project and whose interests and beliefs it aims to reflect. The persistence of such a debate reveals the challenges that lie in fully actualising a secular and inclusive governance structure that respects and represents its citizens’ diverse religious and cultural backgrounds.

This situation calls for a thoughtful re-evaluation of traditions that no longer serve the intended purpose of inclusivity and unity in a modern, multicultural society. Such re-evaluation is not an indictment of Christianity or any religion but a recognition of the need for Australia’s political practices to mirror its democratic, pluralistic, and secular ideals. This ongoing tension between tradition and modernity in Australian politics highlights the need for a more conscious and deliberate approach to inclusivity, one that not only recognises diversity in parliamentary representation but also respects it in practice.

The waning influence of the mainstream media on Australian politics

The downward spiral of media influence in Australia, particularly in the context of political outcomes, reflects a complex interaction between traditional media power and the shifting dynamics of public engagement and technological change. This transformation is evident in the declining ratings and influence of legacy media outlets, which have traditionally played a central role in shaping political debate and public opinion in Australia.

The decreasing relevance of mainstream media is highlighted by significant shifts within the industry itself, such as staff redundancies at major corporations like News Corporation, which is the largest employer of journalists and media staff in Australia. These changes are symptomatic of a broader transformation where the diversification of media platforms and the advent of digital media have fragmented the audience, offering alternatives that cater to a wider array of interests and viewpoints.

This fragmentation is mirrored in the political sphere, where the rhetoric of politicians such Dutton, who frequently frames Islam as a threat, or commentators like Bolt, who perpetuates negative stereotypes about Muslims, no longer uniformly sway the electorate. Instead, there appears to be a growing scepticism towards the media’s portrayal of these issues, suggesting a deeper, more critical consumption of media content by the public. This shift implies that while mainstream media still has the power to reinforce existing prejudices, its ability to convert or significantly alter political views is waning.

The recent political events such as the election of the Albanese government in 2022 and the results of the Voice to Parliament referendum illustrate this nuanced role of the media. In both instances, despite strong media campaigns for opposing outcomes, the public voted differently, indicating that while media narratives can influence public opinion, they do not dictate it. This scenario suggests a more discerning electorate that engages with media content that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs rather than being passively shaped by it.

In addition, the general distaste for Dutton’s public offerings, despite media efforts to bolster his image as a decisive leader, further demonstrates the limits of media influence in modern Australian politics. The public’s disappointment with the Albanese government, on the other hand, reflects not just media criticism but also broader societal expectations and the complex realities of governance.

This evolving media landscape highlights a significant shift from a passive reception of media content to an active, critical engagement by the public. The growing schism between the politicians and media on one side and the electorate on the other indicates a changing dynamic where traditional media must adapt to remain relevant – if, indeed, it is not too late. This suggests that while the media still plays a critical role in political debate, its influence is modulated by a more informed and critical electorate capable of independent analysis and decision-making.

Can political behaviour adapt to the changing media landscape

In the evolving dynamics between Australian politics and media, the relationship, although altered by digital transformations and shifting public perceptions, remains fundamentally interconnected. Politicians, irrespective of their ideological leanings, continue to rely on mainstream media to disseminate their messages, despite the decline in the media’s sway over public opinion. This persistent dependency highlights a deep-seated inclination towards traditional platforms of communication, which, though waning in effectiveness, still hold symbolic and practical value for political figures.

The media’s influence, while diluted, is far from extinguished and maintains a psychological hold over politicians, who often measure their own relevance and the impact of their policies through the lens of media coverage. This is reflected in the attention they pay to headlines and news stories, where visibility in mainstream outlets is still equated with political potency. Consequently, even as the power of these outlets wanes in the digital era, their endorsement or criticism remains a coveted prize in political circles.

This enduring relationship reveals a conservative approach to political communication, where innovation is often sacrificed for familiarity. The reluctance to fully embrace newer, more direct methods of engagement such as social media or alternative news platforms highlights a hesitancy to break away from established norms. This is not only a matter of habit but a calculated decision rooted in the perceived risks of alienating traditional media power bases, most notably players such as Kerry Stokes and Rupert Murdoch. Politicians, aware of the media’s capacity to shape narratives, are cautious of incurring their ire, which can amplify opposition and stir public sentiment.

However, this dynamic is not without its critics and potential for reform. The suggestion of a governmental inquiry into media ownership and the regulation of media licenses points to a growing recognition of the need for greater media diversity and accountability. Such measures, though fraught with political risk due to potential backlash from powerful media conglomerates, could significantly alter the landscape of political communication. By diminishing the concentrated power of a few media entities, the government could encourage a more pluralistic media environment that better represents Australia’s diverse population and offers a wider array of viewpoints.

Taking these issues into account, the challenge is one of courage and political will. The transformation of the media–political nexus would require not only regulatory changes but also a cultural shift within politics itself, where short-term gains through conventional media channels are weighed against the long-term benefits of a more engaged and representative public discourse. The inertia of the status quo is a formidable barrier, with governments often opting for the path of least resistance, which sustains existing power structures and communication strategies.

While the influence of mainstream media on political outcomes may be diminishing, its role within the political process remains significant and the future of this relationship hinges on the ability of politicians to adapt to new realities of media consumption and public engagement. Forging a new path will involve rethinking not just the tools of communication but also the underlying assumptions about power and influence in the digital age. As Australia continues to go through the challenges of racism and Islamophobia, the evolution of this media–political landscape will be crucial in shaping more inclusive and effective governance.