The chaos, corruption and unravelling of an American democracy

Australia needs to decide whether it will move in sync with a changing world or be left behind, clinging to alliances that no longer serve its interests.

Donald Trump is now the president of the United States for a second term, a situation that still requires a double-take and, after the events of 2021 at the Capitol Hill riots – amongst many other incidents during his first term – defies political logic but, as the Americans like to say, it is what it is. The echoes of the chaos of 2017 are returning, except this time, the chaos is deliberate, premeditated, and unrestrained by the checks and balances that once tempered Trump’s first presidency.

The opening days of his return to power have been filled with the same erratic grandstanding that defined his first term: ridiculous territorial demands, aggressive posturing on the world stage, and a calculated descent into authoritarian theatrics. In just the first week, he has threatened to seize the Panama Canal, issued a demand to annex Greenland from Denmark, and renamed the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America.

Bu the United States can’t just seize the Panama Canal: it’s sovereign territory, and any attempt to seize it would be an act of war. Greenland has been under Danish sovereignty for over two centuries: it can’t just be handed over to the United States, despite what Trump says.

These demands are ridiculous at face value but that is precisely the point. They provoke outrage, confusion, and endless media speculation: is Trump serious? Can the U.S. military actually be deployed to seize foreign lands at his command? Can he do this? The moment is reminiscent of the early days of his first presidency when he blustered about NATO, threatened nuclear war with North Korea, and fired cabinet members over Twitter. It is chaos as a strategy, a deliberate means to exhaust opposition, saturate the media cycle, and prevent the public from focusing on his real agenda of extremism.

Trump is making moves that will have profound and lasting consequences for the fabric of American society – behind the smokescreen of his global provocations, he is systematically dismantling civil rights, and his administration has begun its rollback of women’s reproductive rights with unprecedented speed.

LGBTQ+ protections, already eroded in his first term, are now being actively dismantled, with federal agencies ordered to purge diversity initiatives and inclusion programs. His government is rapidly moving toward the wholesale disenfranchisement of marginalised communities, curtailing voting rights through gerrymandering, state suppression laws, and judicial manipulation.

He has stacked his administration with loyalists who are not just corrupt but ideologically extreme, openly espousing white nationalist rhetoric and religious fundamentalism. The Republican Party, having purged itself of dissenters in the wake of Trump’s return, now acts as a rubber stamp, enabling his most draconian policies without resistance.

This corruption is brazen: positions of authority are handed out to unqualified loyalists, many of whom have open criminal records (including Trump) or ties to extremist groups. Government agencies are stripped of career professionals and replaced with sycophants whose only qualification is their unwavering sycophancy to Trump.

Regulations are slashed, environmental protections are removed, corporate oligarchs are given free rein to exploit the economy – America, already teetering on the edge of political and economic instability, is now heading into an era of unrestricted corruption. But despite this, even more alarming is the escalation of Trump’s authoritarian ambitions and fascist tendencies.

He has begun floating plans to round up undocumented immigrants and place them in mass detention centres, with Guantanamo Bay openly discussed as a primary holding facility. The administration’s rhetoric has shifted from coded language to open calls for mass deportations and state-sanctioned crackdowns. The imagery is familiar, in a historical parallel too obvious to ignore. This is not simply about enforcement – it is about intimidation, fear, and the normalisation of state-sponsored persecution. And we shouldn’t worry about revisiting historical cliches or invoking Godwin’s law of Nazi analogies: this is brutal fascism, and we shouldn’t be afraid to call it out, from wherever we are.

Trump’s legal battles, which once seemed like they might prevent his return to power, now appear almost as a footnote of history. The Supreme Court, packed with his handpicked judges, provides legal cover for his most extreme policies. The Constitution, once an obstacle to his ambitions, is now little more than a suggestion. Executive orders and legal loopholes are exploited to strip citizenship from those deemed politically undesirable. And, as usual, there are many contradictions – many of Trump’s closest allies, including his new head of Department of Government Efficiency, Elon Musk, and even his own wife, Melania Trump, benefited from the very immigration policies he now seeks to dismantle. Double standards are no longer a liability in Trump’s America; it is a feature of the system he is building.

However, despite this unprecedented power grab, there are pockets of resistance: Trump’s hold on the federal government is strong, but states with Democratic leadership have begun to fight back. Legal challenges are mounting, with governors refusing to comply with federal directives, and sanctuary cities dig in their heels against mass deportation efforts. The battle lines have been seemingly drawn, and the coming months will determine whether the United States remains a functioning democracy or fully descends into authoritarian rule. The question is no longer whether Trump will push America toward decline; it is whether anyone can stop him before it is too late.

Australia has an opportunity to break free from America’s decline

The farcical nature of United States politics has long been a source of derision – for outsiders – even when the Democrats hold power, but under Trump’s second presidency, it has escalated from dysfunction to something far more dangerous. And it is dangerous, there’s no question about this.

The U.S. is still, for now, the world’s most powerful and influential nation, but it is slipping, not only because of Trump, but because of a long-term decline brought on by political instability, economic stagnation, and strategic miscalculations, concurrent with the rise of China, which will soon overtake the U.S, militarily and economically. While most of the world watches in despair as Trump takes the sledgehammer and angle grinder to democratic norms, Australia is faced with an unavoidable question: does it continue tying its fortunes to a crumbling and increasingly dysfunctional superpower, or does it grab the opportunity to establish itself as an independent, strategically autonomous nation with new and diversified alliances?

The spectacle of Trump’s leadership – an erratic and bombastic return to authoritarian populism, as well as behaving like America’s arsehole-in-chief – may seem like a uniquely American phenomenon, but there are serious implications for Australia. His first term was a warning sign; his second term is where the results of his reckless ideology will come to fruition. The “idiot king” model of politics, the elevation of incompetence as a virtue, the aggressive use of chaos to mask deeper, more insidious policy shifts – these are not just the problems of the United States, but are symptoms of a political virus that has infected democracies worldwide.

History has seen this before: Mussolini in Italy, Hitler’s weaponisation of grievance politics in Germany – leaders who turned democracy into a circus before transforming it into something far more sinister and disastrous. We are seeing this repeated now, and no country that considers itself an ally of the United States can afford to ignore what this shift means for the future.

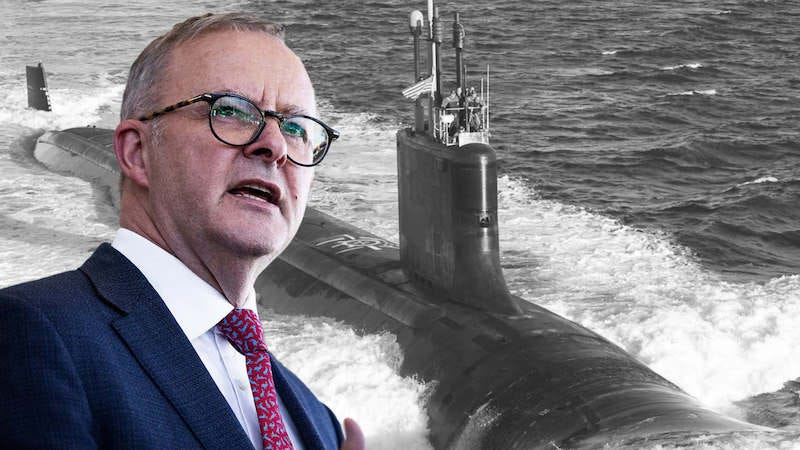

Australia has long been tethered to American strategic interests, often at the expense of its own. The ANZUS alliance, the AUKUS agreement, the constant diplomatic and military alignment – these have been framed as necessities, but in truth, they have left Australia vulnerable to the chaos of the American decline. Trump’s second term is an opportunity, maybe even a final warning, that Australia must reassess its place in the world. Blind loyalty to the United States, especially through AUKUS, no longer serves Australian interests. Instead, Australia must forge new and better relationships – ones that reflect its geographic reality and its economic priorities, rather than outdated Cold War allegiances that are now liabilities.

China, despite the diplomatic strain of recent years, remains Australia’s largest trading partner by a significant margin. Under the Albanese government, tensions have eased, but the deeper question remains: why should Australia continue preparing for military confrontation with a nation it is so economically dependent on?

The AUKUS agreement, sold to the public as a necessary counter to Chinese influence, serves British and American interests far more than it serves Australia’s. The nuclear submarines promised under AUKUS are unlikely to arrive in any meaningful capacity for decades, and even if they do, they will serve more as an extension of U.S. military power in the Pacific than as an asset to Australian defences. The cost – both financial and geopolitical – is enormous, and it locks Australia into an American strategic framework that assumes perpetual hostility with China. But what if that assumption is wrong? What if Australia’s best path forward is not through military escalation but through deeper economic and diplomatic integration with its regional neighbours?

Indonesia, India, and the broader south-east Asian region represent an alternative vision for Australian foreign policy – one based on pragmatism rather than ideological servitude to Washington. Indonesia, a rapidly growing economic power with deep historical trade ties to Australia, should be a priority partner, yet it has often been treated as an afterthought in Australian diplomacy, as though our nearest neighbour with a population of over 270 million, simply doesn’t exist.

India, now the world’s most populous democracy and a rising global power, offers another key strategic relationship that could be cultivated independently of American influence. The Keating-era view of Asia as Australia’s “near north” remains just as true today as it was in the 1990s. A future-oriented Australian foreign policy would recognise that its long-term security does not lie in being America’s proxy in an imaginary Pacific Cold War, but in fostering strong, independent partnerships with the nations that will define the region’s economic and political future.

This doesn’t mean severing ties with the United States entirely: Australia’s relationship with the U.S. is deep, and there are areas of mutual benefit that should not be abandoned. But the blind allegiance, the kind that drags Australia into unnecessary military conflicts, the kind that forces it to take economic hits due to American-led trade disputes, the kind that undermines its own regional credibility – that needs to end. Australia does not need to choose between America and China, or between old alliances and new ones, in the same way it didn’t need to end the relationship with Britain when it veered towards the U.S. after World War II. It needs to assert its own national interests, something it has failed to do for decades due to the sphere of American influence.

History shows that global power shifts move at a glacial pace and don’t happen overnight, but they are happening right now. America’s decline will not be immediate, nor will China’s rise be without complications. But Australia can’t afford to wait: it needs to act now to establish itself as a nation with independent strategic capabilities and diversified alliances. The U.S under Trump is a reminder that tying Australia’s fate too closely to a declining empire is a dangerous gamble: its future is in the Indo–Pacific region, not in the ashes of American exceptionalism.

It’s no longer a question of whether Australia should begin this transition – it’s a question whether it has the political will to do this before it’s too late. The Albanese government could have dumped the AUKUS deal when it first came to office in 2022 but decided not to. It has taken some steps to repair relations with China and deepen engagement with south-east Asia, but the broader shift required is one that will take a lot more political courage.

It means questioning deeply entrenched assumptions about Australia’s place in the world and resisting the pressure from Washington to remain in lockstep with American military priorities. It also means acknowledging the fact that the world is changing and Australia needs to take the crucial steps to change with it.

Trump’s second term will be a test for American democracy but it’s also a test to see if Australia can finally break free from the outdated mindset that has kept it languishing in America’s shadow for far too long. Australia needs to decide whether it will move in sync with a changing world or be left behind, clinging to alliances that no longer serve its interests.

We certainly need to put Australia's best interests ahead of America's.

Maybe we should withdraw from stage 1 of AUKUS under which we get 2 used Virginia class US submarines.

Instead, accelerate stage 2 under which we combine with the UK to build the newer, superior Astute subs.

We need to control our trade routes, and the Astutes are the best way to do it.

Was it ever Democratic??