A historic Labor victory and a devastating Liberal loss

A one-in-a-generation victory has to be savoured as much as possible by the Labor Party but how the Liberal Party rebuilds will be one of the fascinating narratives in the next parliamentary term.

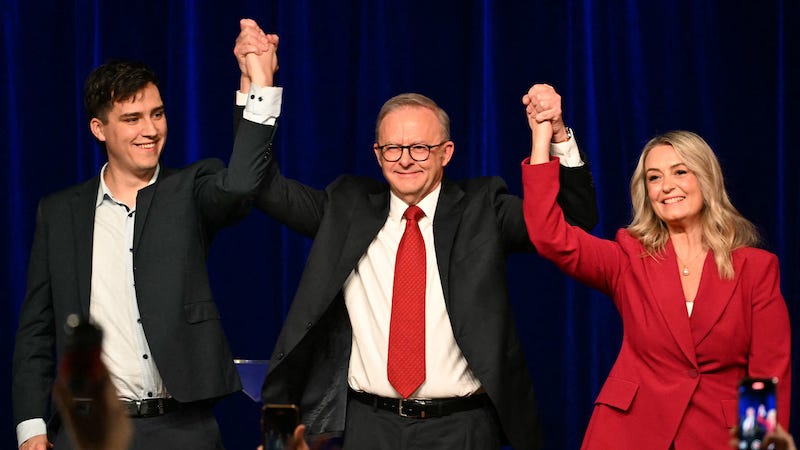

No-one really expected this. There were murmurs, some wishful thinking, a few outlandish predictions – but few expected quite this incredibly one-sided outcome. And yet, many of those wild claims were realised. A number of seats still remain too close to call, but their outcome will do little to change the broader picture: the Albanese Labor government has not only retained power – it has expanded its majority to that of a landslide. On election night, Jim Chalmers’ attempts to suppress his delight on the ABC broadcast were only partially successful, while Liberal senator James McGrath did a ‘Chemical Ali’ job of avoiding awkward questions about his party’s crumbling prospects, constantly suggesting that it was best to wait for more votes to come in, even though it was obvious to everyone that result was well and truly decided.

But perhaps the most striking moment of the evening came not from the winners, but the vanquished. Peter Dutton’s concession speech was unexpectedly gracious. It was humble, even self-deprecating – he accepted full responsibility for the loss, acknowledged the personal journey of his opponent with an empathetic nod to Anthony Albanese’s late mother, and gave his blessing to the incoming Labor MP in his former seat, Ali France. For a man whose political brand has for years been associated with hostility, authoritarianism and culture war skirmishes, the moment was disarming. This was not the Peter Dutton the electorate had come to know: it didn’t undo years of his political brutality, but it did offer a note of dignity to what is likely the closing chapter of his political career.

The magnitude of the Liberal defeat, and the momentary humanity of Dutton’s departure, calls to mind another dramatic reckoning: the election of 1943. The United Australia Party – a precursor to today’s Liberal Party – suffered a historic loss at the hands of John Curtin’s Labor Party. Like the Liberal Party of 2025, the UAP had once been dominant, governing from 1931 to 1940 under the leadership of Joe Lyons. But Lyons’ death, and the flawed elevation of the young and unpopular Robert Menzies, precipitated a rapid decline. Menzies, too arrogant for the times, was soon forced to resign, retreating to the backbench in disgrace. The UAP floundered under ageing and uninspiring leadership, was seen as a servant of big business, and had become disconnected from the national mood.

The parallels are remarkable: a party led by unpopular and ill-suited leaders. A steady exodus of moderates. A loss of identity created by years of ideological games. The 1943 election wasn’t just a defeat – it was an existential crisis. Menzies, to his credit, recognised this. In 1944, with a mix of business and conservative allies, he created a new party: the Liberal Party of Australia. It would spend the next several decades dominating Australian politics, with only a few interruptions.

That success now feels like ancient history. The modern Liberal Party has purged its moderate flank. The last remaining centrists, Bridget Archer and Keith Wolahan, were swept away in the Labor surge through Tasmania and Melbourne. Calls for introspection during these moments are usually drowned out by demands to shift ‘further to the right’ – a strategy that continues to produce diminishing returns, not just federally, but in state and local contests. Outside its echo chamber, the party’s alignment with the fringe ideas of the Institute of Public Affairs is toxic. And much like the UAP of the 1940s, the Liberal Party of 2025 is beginning to resemble a political museum relic – one that needs reinvention and replacement, to remain relevant in an Australia that has long since moved on.

Labor’s discipline, consistency and the power of incumbency

While the Liberal Party unravelled under the weight of internal discord, miscalculation, and ideology, the Labor Party ran one of the most disciplined and effective campaigns in recent memory. It wasn’t flashy. It wasn’t revolutionary. But it was relentlessly consistent, grounded in pragmatic messaging, and focused on projecting stability – exactly what a risk-averse electorate seemed to want in 2025.

Labor understood the strength of incumbency and used it carefully. Anthony Albanese positioned himself not as a radical reformer, but as a steady hand during uncertain times. His campaign leaned on achievements: real wage growth, declining inflation, a strengthened Medicare system, and modest gains in housing affordability – presented not as solved crises, but as challenges being actively and competently managed. It was a subtle, yet powerful narrative: we know things aren’t perfect – but trust us, they’re getting better.

Critically, Labor resisted the temptation to overreach. While the Liberal campaign descended into increasingly dystopian warnings about national collapse and social decay, Labor stuck to measured optimism. Albanese avoided major gaffes, kept controversial ministers largely out of the spotlight, and maintained a clear focus on kitchen-table issues: wages, health, cost of living, and economic certainty. Rather than getting drawn into culture war traps set by the Coalition – on nuclear power, race, gender, and immigration – Labor avoided them altogether. It was a deliberate and disciplined campaign, one that left the Coalition shouting into a void while the electorate turned away.

Dutton’s undoing: Missteps, misjudgements and alienation

Dutton’s defeat was not the result of a single event or tactical blunder – it was the culmination of choices over the years that alienated the very voters he needed to win over. Much has been made of Dutton’s overt embrace of Trump-style politics, from the hardline nationalism and race-baiting dog whistles to the stifling culture war rhetoric that felt increasingly imported from the worst of American public debate. But as the United States continued its slide into dysfunction, many Australian voters took a long, hard look and decided this was not an agenda they wanted to follow.

The more immediate blunder came even before the campaign commenced, when Cyclone Alfred struck Queensland. While thousands of residents braced for damage and disruption, Dutton – whose own electorate of Dickson was affected – chose to leave the state for a fundraising event in Sydney, surrounded by corporate donors and political elites. The optics were devastating: the man who wanted to lead the country appeared to abandon his constituents at a moment of crisis. Even for voters who may have tolerated his abrasive style, this act of detachment seemed to be a final breach of trust. For many in the seat of Dickson, this was the moment Dutton forfeited the right to represent them.

But his real downfall may have started much earlier, during the 2023 Voice to Parliament referendum. Dutton’s decision to lead the “No” campaign was, at the time, widely seen as a political gamble – a chance to rally the base, weaponise division, and further isolate Labor from conservative and regional Australia. The campaign succeeded in defeating the Voice proposal, but the victory came at a steep cost. Public sentiment shifted rapidly in the months that followed. Voters – particularly younger Australians, women, Indigenous communities, and urban moderates – began to view the “No” campaign as rooted in deception, fearmongering, and barely concealed racial undertones. Dutton, became the face of that campaign, and for many Australians, he came to embody a form of politics they no longer wished to be associated with.

Perception became reality. Even if Dutton was not personally racist – and by all accounts, many colleagues insist he is not – the image was indelibly stamped. The political stain was compounded by his dry, often sarcastic manner, which read less as wit and more as disdain. For younger voters and women especially, Dutton’s style felt combative and cold. He was a man out of step with the country he wished to lead.

In the end, Dutton’s concession speech revealed much about his political journey. He made no mention of his leadership, his years in opposition, or even his electorate. Instead, he claimed his career highlight was his time as defence minister – a position built on security, militarism, and fortress politics. It was an interesting admission: for a man who led his party through one of its worst defeats in decades, and who could never quite shake his image as a political enforcer, there was no prime ministerial grace note waiting for him. Just the final irony of a career defined by division, ending in a moment of unexpected humility. Dutton wasn’t beaten by fate – he was, in many ways, destined never to lead.

Rebuilding the Liberal Party rabble

By any sober measure, the Coalition was never going to win the 2025 election. Requiring a net gain of 22 seats, the path to majority government was just a mathematical fantasy. But that doesn’t mean the campaign had to be wasted in this way. A smarter opposition could have used this parliamentary term to consolidate its base, target winnable seats, and prepare a compelling policy vision that could lay the basis for the next election in 2028. Instead, the Liberal Party drifted through the campaign with policy offerings and costings that were weak and barely held up to scrutiny, vague promises, and a strategy that seemed to rely more on media favours and culture-wars outrage than on genuine public engagement.

While Labor presented discipline, consistency, and policy credibility, the Liberal campaign often looked like a disorganised imitation of past mistakes. The old trick of ‘muddling through’ – which had worked to a degree in 2013, 2016 and 2019 – had finally run its course. The political landscape had changed, and the Liberal Party hadn’t kept up. In contrast, Labor had done the hard internal work: it cleared out underperformers, reconciled internal factional tensions, refined its policy program, and learned the lessons from the 2019 defeat and the Voice referendum debacle with a more cohesive, future-oriented identity.

The Liberal Party, by contrast, lacked discipline, clarity, and self-awareness. It seemed complacent – still convinced that culture war slogans and reactionary talking points could substitute for substance and be enough to win. Where Labor had learned and adapted, the Liberals had regressed. It no longer knew who it was fighting for. Menzies once spoke to “the forgotten people” – the middle class that felt ignored by elites and the working class alike. John Howard found resonance with “Howard’s battlers” – aspirational blue-collar voters. Even Tony Abbott’s crude appeal to “Tony’s tradies” had, for a time, connected with a segment of the electorate.

Dutton’s Liberals, however, built their identity around a hollow rejection: they were not woke, not elite, not educated. They defined themselves by opposition – against imagined enemies rather than for real constituents. But these enemies were never clearly defined, and the concerns they obsessed over bore little relation to the actual anxieties of the electorate. With cost-of-living pressures, housing insecurity, interest rate worries, and international instability front of mind, the Coalition chose to shout about gender identity and ‘cancel culture’. Anti-woke. The disconnect was profound. And it was political suicide.

The Liberal Party now enters what could be a long, painful period of introspection – or further denial. Dutton is gone, and the names being floated as successors don’t inspire any confidence at all. What the party requires is not another media-friendly placeholder or another ideologue from the fringes – it needs a leader with the courage to dismantle what no longer works and build something new. That will mean staring down the far-right faction, which is already attempting to rebrand itself as centrist while pushing the party even further into irrelevance.

What is required is nothing short of a Menzies-style reimagination. When Menzies founded the Liberal Party in 1944, he correctly identified a growing middle class that wanted stability, autonomy, and dignity. But that middle class – stable, secure, upwardly mobile – has all but vanished in contemporary Australia. A new Liberal leader will have to look more deeply, and honestly, at what Australia is now: fractured by inequality, energised by diversity, and far less tolerant of dogma. This leader must shape a party not for a fantasy electorate, but for the real one that exists today – and govern with a vision that appeals beyond donors, media backers, and culture warriors.

The right has failed to do this for decades. If it cannot now, the Liberal Party may fade into the same irrelevance that consumed the United Australia Party before it. While we can’t focus too much on the losers in this election – this is a one-in-a-generation type of victory for the Labor Party and must be savoured as much as possible by their supporters – how the Liberal Party rebuilds itself will be one of the fascinating narratives of this next parliamentary term.

Thanks David for your historical perspective on the beginnings of the Liberals and the discrediting of the UAP. Who knows what might come next? Will there be a new Party, or will the remainders try and rally and fight on for another election?

With your point on the loss of Bridget Archer, I think she was an exceedingly rare MP in the Parliament willing to cross the floor and vote against their own party.

Like the independents she remembered that she represented a constituency and not necessarily the party. That is something to be admired and contrast with the ALP which imposes suffocating internal discipline. Time will tell if the new MPs have some new ideas or are just yes men and women.

The Liberals and the Nationals need to separate whilst they are in opposition. This would allow the Liberals to develop a policy menu based around cities. Though this may not work because of the influence of angry old men on the Liberal Party.