Breaking up is hard to do: the end of the Coalition

If the Coalition parties are to govern again, they need to redefine who they are, who they represent, and how they can engage with the new and emerging forces in the Australian political landscape.

The break-up of the Coalition between the Liberal Party and the National Party wasn’t unexpected; if anything, it was overdue, an inevitable consequence of years of diverging political interests, regional priorities, and incompatible ideology. A classic case of the tail wagging the dog. What once functioned as a pragmatic electoral partnership, created after World War II to consolidate the anti-Labor vote, had become increasingly strained in recent years. The 2025 federal election result – a historic landslide against the Coalition, reducing it to just 43 seats – exposed these tensions even further.

The Liberal Party was left with only 28 seats in the 150-seat parliament and after such a crushing loss, the party faced a choice of retreat furthering into the comfort zone of hard-right populism that alienated centrist voters – as the 2025 election results showed – or to rebuild from the political centre where elections are won. The choice seems obvious but political parties rarely make the obvious choices, especially when there are so many considerations to take into account.

For the Nationals, the story is a different one but still complicated. With 15 seats – immune from the urban collapse that devastated their senior partner – after the election, they emerged with a greater share of the Coalition’s representation than ever before and under normal proportional logic, this would have entitled the Nationals to at least a third of the positions in the Coalition’s shadow cabinet. While technically still the junior partner, they’re not as junior as they used to be – relatively speaking – and they would have wielded a level of influence that the Liberals would have considered unpalatable. Barnaby Joyce returning as a senior shadow minister within the Coalition, pushing nuclear policy, anti-renewables and ramping up the climate wars again? No thank you. It’s no wonder the new Liberal Party leader Sussan Ley pushed a hard bargain and the Coalition collapsed.

But this is more than a numbers game or, as John Howard use to call it, the ‘iron laws of arithmetic’. The philosophical divide between the parties has widened over the past few decades where the National Party no longer speaks solely for farmers and rural producers; instead, it’s become increasingly aligned with resource extraction industries and multinational mining interests, gaining the support of wealthy miners such as Gina Rinehart, a long way away from its historical image as an agrarian populist force. Meanwhile, the Liberal Party – once the champion of economic liberalism and urban middle-class stability – has lost its ideological bearings, and since around 1995, has veered towards culture war politics and doctrinaire conservatism, no doubt influenced by the National Party.

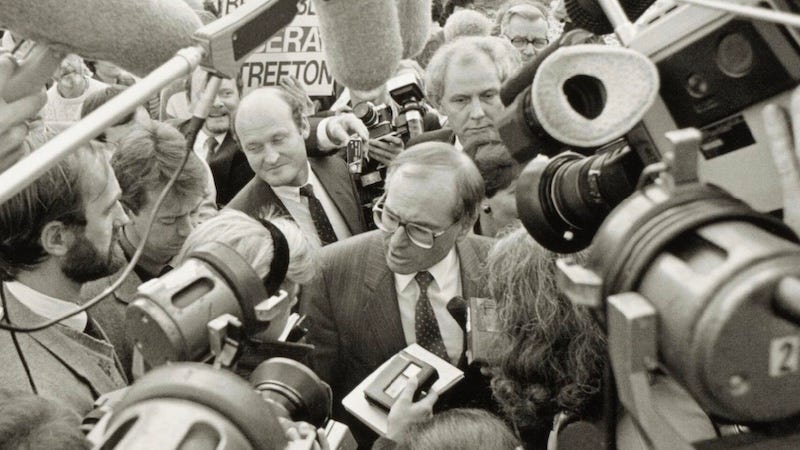

The Coalition arrangement, first negotiated in 1946, has always been more about power than policy – it was designed to secure majorities on the conservative side of politics and offer a united front against Labor. And while Coalition agreements essentially only come into effect when the parties are in government, the mechanics of that relationship has remained shrouded in secrecy, an undemocratic feature in an otherwise open political system. The last time Coalition had some kind of separation was when the parties campaigned separately in the 1987 federal election, due to deep personal and policy rifts between Liberal Party leader John Howard and Nationals leader Ian Sinclair. Even then, it was a temporary separation when they realised after the 1987 election loss, that the parties united would have a greater chance of electoral success, even if that success didn’t arrive until the 1996 election, nine years later. This split in 2025 feels more profound.

It’s not yet clear who gains from this new political landscape, and it will take a while to work this out, especially in the context of any form of centre-right alliance being so far away from being able to form government, realistically, not until at least 2031. This separation might be the pause both parties need to reflect, recalibrate, and reform. But the key issue is that the Australian right is no longer a unified force and whether this leads to renewal, a realignment, or continued fragmentation will be one issues to look out for in this next parliamentary term.

The divisions on the right

For years, the Coalition between the Liberal and National parties papered over a high level of incompatibility – two parties with conflicting ideological instincts bound together more by political necessity than shared vision and, in some cases, different styles of leadership and personalities. This separation in 2025 is not just about Howard’s ‘electoral arithmetic’ or personal rivalries; it’s about a deeper schism within Australian conservatism. Now, that the federal election has exposed these fractures, both parties will need to go down different paths.

The reality is that both parties has been a drag on each other: the Nationals have long been viewed as too socially conservative and too beholden to regional and resource-sector interests for many in the urban-centric Liberal Party, as well as harnessing a brand of retail politics and anti-wokeness that is now deemed to be electorally reckless. At the same time, sections of the Liberal Party – particularly in those few remaining inner metropolitan areas – were seen as too progressive on climate, gender equality, and multicultural issues to be comfortable partners with the Nationals. These strains were evident even back in 1987, when the parties last campaigned separately, but today, these differences are even more deep. The Liberal Party has become a playground for internal factions, especially with the greater influence of religious groups and the hard-right in Victoria and South Australia, undermining the party’s identity as a broad, secular party of liberal economic and social values.

While the Nationals are still the smaller party, if the Coalition had remained intact, their influence would have increased far beyond what would have been tolerable to the Liberal Party. After the election, they pushed to keep nuclear energy on the policy table, demanded conservative social positions, and hardened the Coalition’s overall stance on issues such as climate and regional development. Their power also has stability: they lost only one seat – Calare – in the 2025 election, compared to the catastrophic collapse of the Liberal Party, which lost 15. But Ley has refused to concede more ground and perhaps it’s the right decision.

Practically, the implications are great: as the formal Opposition, the Liberal Party will hold all shadow ministerial positions – along with the salaries, staffing, and parliamentary privileges that come with them. That structural advantage gives the Liberals an opportunity to reposition themselves as a centrist party, shedding the baggage of rural populism and reactionary wedge politics. Whether they take that opportunity is another question, but the electoral logic of this is clear: the voters are in the centre, as they always have been within Australian federal elections. The hard right and far right might dominate headlines and have the loudest voices, but this is primarily a culture of complaint and whinging, and they rarely win enough seats to make a difference. For all the bluff and bluster from One Nation since its formation in 1997, aside from its initial success in the 1998 Queensland election – where it won 11 seats and gained 22 per cent of the primary vote – its electoral impact has been minimal. The party continues to exist on the fringes: a culture of complaint can only take a political movement so far.

For the Nationals, their future is more delicate. While their existing seats are relatively safe – supported through strong local networks and entrenched regional loyalties – the party now finds itself locked out of the formal structures of opposition. With fewer resources and less authority in Canberra, their role risks shrinking to that of a noisy, regional pressure group. There will be pressure to align with fringe right-wing parties such as One Nation, Clive Palmer’s Trumpet of Patriots, the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, or other fringe dwellers. But the federal election result should also serve as a warning: these parties failed to make any meaningful electoral gains, and the politics of grievance and identity did nothing to shift the electoral fortunes beyond isolated pockets around the nation.

The Nationals leader, David Littleproud, is now facing the toughest leadership test of his career and needs to decide whether the Nationals should double down on ideological purity or take on a more constructive role in regional advocacy. Without the platform of a formal Coalition, and without access to shadow cabinet roles, there is the risk of irrelevance for the Nationals, where they become a fringe player themselves. This dissolution of the Coalition might free up the Liberal Party to rebuild according to true values of liberalism but for the Nationals, it could be the beginning of a long and slow path towards political oblivion.

The mathematics and impossible permutations of power

The end of the Coalition also raises a difficult question for the Liberal Party: where do they go from here? With just 28 seats in the House of Representatives, their path back to government is not only steep but difficult strategically. Without the National Party, the numbers just don’t add up – not without creative and politically unlikely alliances. History offers only three examples where the Liberal Party would have been able to govern in its own right: 1975 under Malcolm Fraser, 1996 under Howard, and 2013 under Tony Abbott and, even then, these were bare majorities. These victories were built on landslides that brought the Nationals along for the ride, not around them and the idea of governing alone in the foreseeable future, without either formal or informal support, is in the land of fantasy.

Today, the crossbench matches the Liberal Party seat for seat: 28 MPs; 15 from the National Party, 10 independents – most of these are community independents – plus one each from Katter’s Australian Party, the Australian Greens, and the Centre Alliance. For the Liberals, this represents not just a challenge of numbers but an existential one. If they hope to return to government, they need to either rebuild new alliances or engineer a seismic electoral shift of grand proportions. The traditional fallback of the National Party is now off the table, although there have seem some murmurings within the party that there is group that wants to re-establish the Coalition within weeks. If that fails to materialise and the dissolution continues, that leaves the independents for a potential alliance.

The prospect of the Liberal Party reaching out to the community independents might once have been unthinkable, especially under the dominance of hard-right figures who saw these independents not only as political opponents, but as ideological enemies. That’s two elections in a row – 2022 and 2025 – where the ‘teal’ independents have been rubbished by figures such as Scott Morrison, Josh Frydenberg and Peter Dutton.

But if the Liberals want to reposition themselves as a moderate, centrist party – as many believe Sussan Ley is now attempting to do – those overtures might become more plausible. After all, many of these independents share centre-right economic instincts and a pragmatic approach to governing. What separates them from the Liberals isn’t just policy, it’s the culture, trust, and integrity, as well as their approach to addressing climate change issues.

However, the numbers are still massive. For the Liberal Party to win government in 2028 in any shape or form, the Labor government would, first of all, have to lose 19 seats. That’s an enormous swing to ask of an electorate, especially following such a decisive result in 2025. Then, all other things being equal, it would have to build a motley collection of Liberal, National and independents and somehow entice the Greens over to their side. It’s a big ask.

It’s more than likely going to have to be a two-cycle strategy, just to become electorally competitive: slow and steady gains, a party rebrand, and building bridges with those disillusioned voters who abandoned the Liberal Party in inner metropolitan areas. It’s a long game, and a risky one – especially when the Nationals, now estranged and more likely to move further to the right, might end up contesting against Liberals in regional fringe seats and drag the broader conservative brand into further fragmentation.

There’s been much talk about breakdown of the two-party system in Australia, and with the 2025 federal election showing that around 33 per cent of the electorate voting for someone other than Labor, Liberal or National, there is merit in this idea. Certainly, signs of that shift are appeared but it’s affecting, as this stage, one side of politics: the splintering is happening almost entirely on the right.

The centre and centre-left of politics has largely held firm. Labor remains structurally sound, the Greens have a stable voter base, and the progressive independents – while not a formal party or alliance – operate with a shared set of values. In contrast, the right is fragmenting into a patchwork of parties and personalities: Liberals, Nationals, One Nation, Katter, Shooters and Fishers, and now a growing assortment of populist micro-parties and far-right agitators.

That fragmentation might reflect broader changes within the electorate – the diversifying values, economic pressures, and generational shifts – but unless the right finds a new unifying vision, it will keep drifting away from centrist values. The Liberal Party can’t rely just on Howard’s idea that politics is ‘governed by the iron laws of arithmetic’. If it wants to govern again, it must do more than rebuild its base – it needs to redefine who it is, who it represents, and how it relates to the new and emerging forces in the Australian political landscape.

Interesting post and enjoyable to read, thanks. I think the politicians and voters of the two major political forces in Australia in recent times, the L/NP and Labor Party, themselves have always internally been coalitions of people with varying opinions, sometimes difficult to shepherd. For a long time there was nothing more democratically explosive in Australia than an ALP State conference, tomato throwing and all. Most Greens voters probably came from the Labor side originally but now their second preferences are split between ALP and L/NP. Their presence on the left of the ALP in the spectrum of opinion creates tension inside the ALP but also allows the ALP to position itself as a centrist force. The L/NP didn’t have this ability and one functional value of Clive Palmer’s noisy party du jour (United Australia last time, Trumpet of Patriots this time) and One Nation, regardless of their vote percentage was to create a (bogus?) perception that the L/NP is somewhat “moderate right”. The decision to split the Coalition makes this situation a reality - with the Nats being positioned to the right of the Libs - once the Libs policies shift back to the centre. That may not disadvantage Nats voters if the Nats vote as a bloc with the Libs on things that are vital to rural communities. It could, however, disadvantage any moneyed interests who were influencing Nats policies and through them the L/NP Coalition’s policies (and the Libs electability). The mystery factor in all this is the ex-Liberal teals, most of whom were returned in 2025. Will they rejoin a more centrist Liberal Party, form their own party (maybe on a new model), or continue as they are? (Good point by Michael’s Curious World.)

Can the Liberals move far enough back towards the centre to unite with the 'teal' Independents, who might once have been moderate Liberals?

Once Malcolm Turnbull was a moderate Liberal who became PM, but was then toppled by right-wingers like Dutton and opportunists like Morrison.

Just as Labor can co-operate with the Greens, can the Liberals co-operate with the Independents?

Seems a tough ask right now.

Biggest danger for Labor is dominance breeding complacency and egos exploding into infighting. How long will Chalmers be patient?